Jeremy Barnes

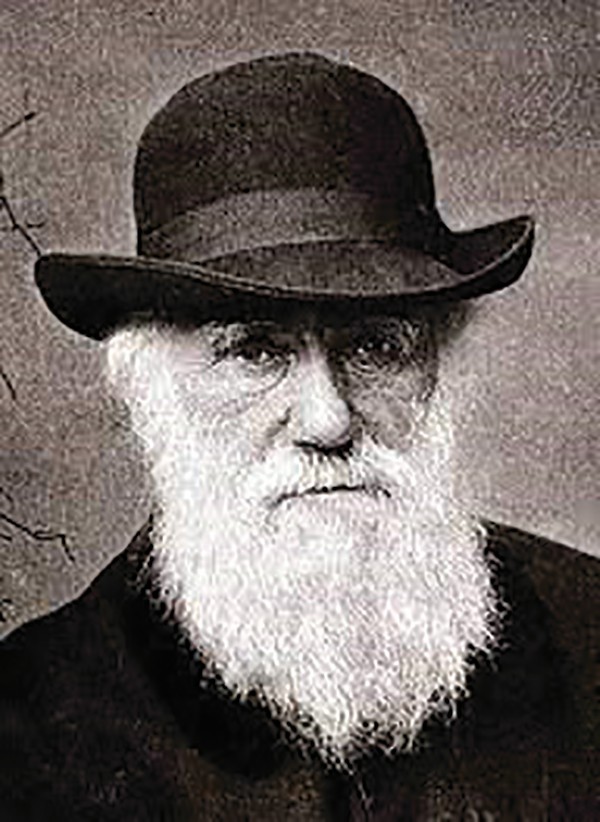

“Don’t you think it would be sad if the human race suffered a catastrophe?” Charles Mann asked the late, great evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, No, she responded, arguing that in a million years the planet will be fine – we just won’t be living on it. Then she added, “Besides, it’s the fate of every successful species to wipe itself out.”

One of Darwin’s laws is that biological processes like evolution apply to every species, from protozoa to people. If one puts some bacteria in a petri dish filled with nutrients, they will eat and multiply until they hit the edge of the dish, and then either starve to death or drown in their own wastes. Because biological laws apply to every creature, Margulis suggested, the same will happen to us – it’s inevitable. For it not to happen we would have to be special; we would have to be unlike every other creature in that the rules of nature would not apply to us.

Let’s project 40 years into the future, when the earth’s population may exceed 10 billion (which will include some of you reading this article) and ask what kind of world it will be. This is the essential question Charles Mann asks in his most recent book, The Wizard and the Prophet, which is a portrait of two little-known 20th-century scientists, Norman Borlaug and William Vogt, whose diametrically opposed views have shaped our ideas about the environment and the choices we face as to how to live in tomorrow’s world.

The first view, what Mann labels the Prophets, follows William Vogt, who was in many ways the founder of the modern environmental movement, a crusade that Mann describes as ‘the only enduring ideology of the twentieth century.’ Vogt’s fundamental contribution was to say that the planet has limits within which we have to live. According to data aggregated by the Global Footprint Network, it takes the biosphere a year to produce what humanity habitually consumes in roughly eight months – a situation that is logically unsustainable. And yet we persevere with what the British psychologist Michael Eysenck calls the ‘hedonic treadmill,’ holding out the hope that we can somehow purchase or will ourselves out of the crisis of diminishing returns. Rather, Vogt urges, put on your sweater. Turn down the thermostat, eat lower on the food chain, consume less rather than produce more, eliminate toxins, reduce and recycle waste, protect biodiversity, live close to the land and protect local communities. Small is beautiful, live lightly on the soil and work with nature rather than overwhelm it. Such a vision – a network of self-sufficient citizens guided by ecological precepts – conflicted with the prevailing perception of the good life and evoked epithets like ‘tree-huggers.’

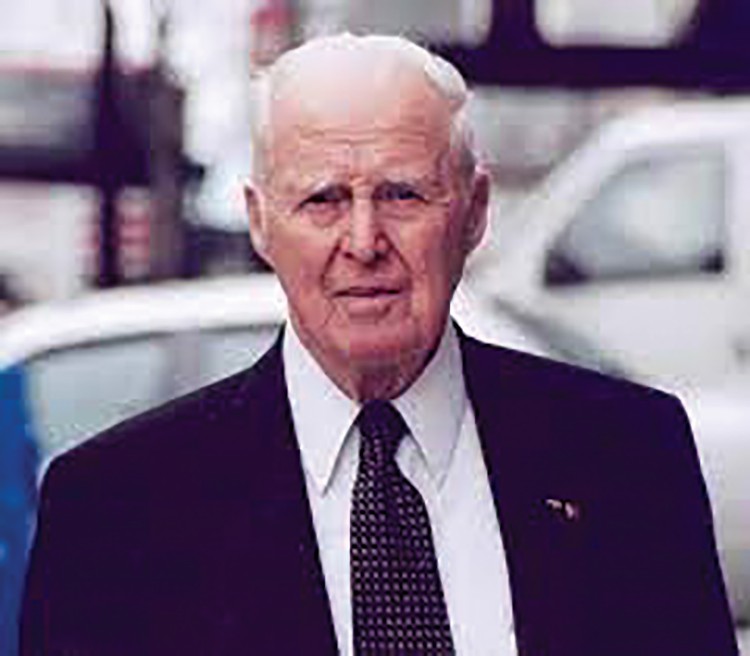

The Wizards are the heirs of Norman Borlaug, an agronomist and humanitarian, who exemplified the idea that science and technology, properly applied, will let us produce our way out of our problems. In 1942 he took up an agricultural research position in Mexico, where he developed semi-dwarf, high-yield, disease-resistant wheat varieties. Combined with artificial fertilizers and intense irrigation, Mexico became a net exporter of wheat by 1963. Between 1965 and 1970, using a new variety of rice developed with Borlaug’s assistance, yields nearly doubled in Pakistan and India, greatly improving the food security in those nations. Thus Borlaug has been called “the father of the Green Revolution” and is credited with saving over a billion people worldwide from starvation, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. The response of the Prophets to a technology that significantly increased the amount of calories produced per acre of agriculture, is unrelenting. Since fertilizers are essential to the Green Revolution they forever changed agricultural practices, not only in terms of never-ending streams of nitrates, potash and potassium that run off into the water system, but also the large industrial complexes that were needed to produce chemicals on a sufficient scale.

Irrigation is also essential in that rivers need to be dammed and diverted, sending water to drier areas. California is a prime example of the manipulation of water resources for the Central Valley and the crises this has caused state-wide in increasing times of drought.

In addition, the development of high yield varieties meant that only a few species of corn, wheat or rice were grown. In India for example there were about 30,000 rice varieties prior to the Green Revolution; today there are around ten, all the most productive types. By having this increased crop homogeneity there were not enough varieties to fight off disease and pests, meaning that pesticide use grew as well.

The use of Green Revolution technologies exponentially increase the amount of food production worldwide, which is advantageous for those living on the edge yet also increased the global population dramatically, thus adding to the problem that was the initial concern. Ironically such technology is denied to places like many African countries that do have the infrastructure, governmental efficiency and security of other nations.

And let us not forget the small scale, traditional farmers who struggle with debt and crop failures in the face of large scale industrialization and corporate control. Al least 300,000 farmers across India have committed suicide since 1995 – that’s almost 40 a day – often by drinking the very pesticides that are, by their price, the cause of their failure and sense of shame.

Prophets look at the world as finite and people as constrained by their environment. Wizards see possibilities as inexhaustible and humans as wily managers of the world. One views growth and development as the lot and blessing of our species; others regard stability and preservation as out future and our goal. Vogt believed that ecological research has revealed our planet’s inescapable limits and how to live within them. Borlaug believed that science could show us how to surpass what would be barriers for other species.

Particularly important, the two sides have two different ideas of liberty. Wizards think that people are independent individuals who are most free when they have maximal choice – they can reinvent themselves endlessly, breaking through all barriers. Prophets think humans are by nature social and biological beings and true freedom lies in recognizing and celebrating our essential character, as creatures bound into a community, as a species in a web of other species.

What brought this to mind was the January issue of Bee Culture in which an article by Dr. Tom Seeley (a Prophet) on Darwinian Beekeeping, was sandwiched between three articles on new technologies for use in the hive (the Wizards.) After summarizing the history of the honey bee, going back to East African fossils that are 1.6 million years old, Seeley writes, “Wilk and managed (colonies) live under different conditions because we beekeepers, like all farmers, modify the environments in which our livestock live to boost their productivity. Unfortunately, these changes in the living conditions of agricultural animals often make them more prone to pests and pathogens.” I would add that most of those modifications have been made for the benefit of the beekeeper rather than the long term health and survival of the bees.

Malcolm Sanford, in his article titled Record Keeping with Smart Phone Apps, writes, “In this technological age, the amount of data that is possible to collect is mind boggling. Thus more than ever beekeepers risk being swamped by almost infinite possibilities when it comes to making management decisions.” In the same issue Engelsma et al assess the increasing number of electronic hive scales available, while Cazier et al describe the data sharing risks and rewards for commercial beekeepers.

It is customary, in today’s world, to give equal consideration to both sides and to come up with a compromise, in this case more environmentally friendly hives for the bees with the use of technology for the benefit of the beekeepers. Yet the current trend seems to be more of the latter and less of the former. I am strongly attracted by Seeley’s argument and am experimenting with some major modifications to the Langstroth hive, first suggested by David Papke, that are more akin to the environment feral bees will choose for themselves. I do have scales under three of my hives as part of an experiment by Pennsylvania State University to assess the relationship between colony health and the surrounding environment; otherwise my technology consists of a hive tool and a smoker. I have to borrow my wife’s smart phone to record the data from the hive scales.

In terms of the bigger question posed by Vogt and Borlaug, humankind is capable of solving this dilemma. Simply feeding 10 billion people – most of whom will be middle-class – will require prodigious social and economic changes. The issue is whether we will do it, and if so, will we do it in time. On that, the jury is out.