Beekeeping Techniques for the Faint-Hearted Beekeeper

James E. Tew

My bees are ageless. I am not.

As have you, I have been through many age-related events in my life. I learned to ride a bike and to swim. I was awarded my driver’s license. I grew old enough to vote. Multiple times, I graduated from various educational programs. I was in the military. I married, and my wife and I produced three daughters. I got my first bees. I earned tenure at my university. I worked for decades there and then retired. I became a grandfather. My social security started. I am now at this point in my life – an old guy with a pronounced interest in all things honey bee.

Readers, I don’t have a lot of benchmarks left, but there is still at least one that remains – next spring, I will have kept bees for fifty consecutive years. I readily acknowledge all of you who have been with the bees even longer than I, but still – for me – fifty years is a long time. Through all my seventy-three years, I have changed a lot, but my bees are ageless. They have hardly changed at all. They still sting. They still swarm, and they still seem to hate their queens.

Traditional beekeeping

The thing I am calling “Traditional Beekeeping” is a moving target. What was traditional when I began beekeeping all those years ago, has moved to different traditions now. No more embedding wires in foundation or producing honey in basswood sections. No more honey in metal 60# tins. Nope, today’s beekeepers are all about varroa control and foundation inserts and plastic honey jars, or yet another app for our new primary hive tool – our mobile phone.

Fifty years from now, when I am one hundred twenty-three years old, all of today’s “modern” traditions will seem quaint. Again, the thing I am calling “Traditional Beekeeping” is a moving target. Your bee target will move, too.

I can only call it an “Epiphany.”

During late August, as I have done during so many Augusts past, I went to my bees to take, what I viewed as, my part of the honey crop. As I have always done, I employed traditional techniques to produce and harvest this surplus honey. My hives are on hive stands about twenty inches from the ground, and I use maybe two to three deeps as brood nests. My honey supers – filled to greater or lesser degrees – were either deeps or possibly regular supers, and most of the hives housed about 65,000 – 75,000 bees. These were nice, big, producing colonies.

With complete honesty in mind, this honey removal procedure can only be described as sticky, heavy, tiring work. As is always the case, the bees took a very dim view of my actions. I abruptly had a moment of clarity.

Current Traditional Bee Management Theory:

- Big colonies are good colonies.

- Big honey crops are big rewards.Eliminate swarming.

- More colonies are better than fewer colonies.

- Only the best-bred queens are proper queens.

- In all ways, more, bigger, better, heavier, yet even more is better

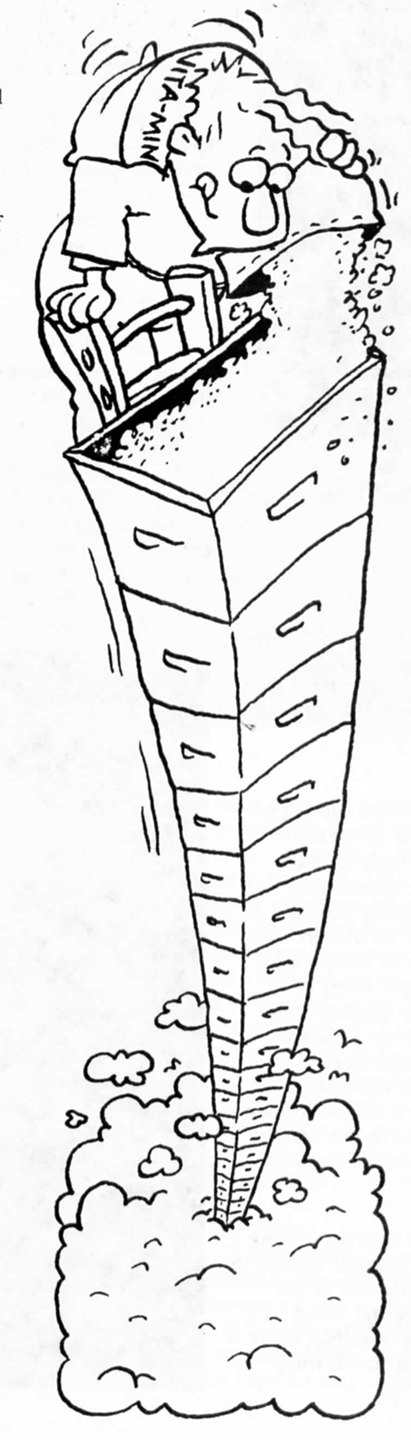

On that day, as I struggled, trying to get a full deep of honey off a hive that was five deeps high, twenty inches off the ground, and defended by thousands of hostile and confused bees, I was struck by the abrupt, clear realization – I shouldn’t do this anymore. Indeed, I don’t even want to do this anymore.

I have five or six titanium screw anchors in my left shoulder. I have hearing aids in both ears. I have surgical steel staples embedded in my gut. One-third of my teeth have been root-canaled. Cataracts are forming in both my eyes. I am probably forty pounds overweight, and my knees hurt.

On this late August day, I was trying to implement traditional beekeeping as I had always practiced it for the past forty-nine years. For all those years, for me, it was the correct way for me to keep bees. I can only write that I suddenly instinctually knew that I should not be doing this anymore. “If you tear your shoulder up again…..!!” This work was too strenuous and the demands on my aging body too great.

But here’s the problem – I am not quitting my relationship with the bees. Yet, the bees are not going to change, so I will have to do all the changing. I can only call this realization an “Epiphany.” Yet, another milestone.

My first action as a Senior Citizen Beekeeper

As I see things for me, the first action that I should take at this time in my life – discard the concepts in the Current Traditional Bee Management Theory that I listed above. Those are the divining concepts for younger, healthier beekeepers. My youthful time has come and gone, but I’m still here.

Essentially, my personal working senior citizen bee management concepts would be something like:

- Single deep colonies can be good colonies.

- Some surplus honey is good, but not required.

- Occasional swarms may help control varroa populations.

- Manage fewer, smaller colonies more easily and efficiently.

- Don’t aggrandize queens – average may be good enough.

- In general, don’t worry about the small stuff.

Then my wife said…

My wife and proofreader said that my comments to this point would be discouraging to young beekeepers. Heavens above, that is not my intent! Young beekeepers, have at it. Build. Develop. Grow. Enjoy. I certainly did when I was your age. Through my years, I have tried most common aspects of beekeeping such as queen production, pollen collection, comb honey production, candle making, homemade woodenware, top bar hives, and so much more. I am now at a point where it seems to be time to again try yet some other aspect of beekeeping – smaller scale, lighter weight beekeeping.

But what I immediately run into is that the generalized management theory for smaller scale, lighter weight beekeeping is not clearly and readily documented. But this is where I am in my bee life, and this is what I would like to write about for the next few articles as I slog through the fog of the unknown.

Beehives come in one size – extra large

Even as a younger, more physically fit man, I could see the reality that successful bee hives were thought to be big, populous monstrosities. In various presentations, through the years, I made light comments about how much more often smaller, more agreeable colonies got inspected in my apiaries. The behemoth units that required moving a hundred pounds of honey supers to get to the brood nest got checked less frequently.

Seven years ago, in 2014, I wrote an article for Bee Culture magazine entitled, Are Big Colonies Always the Best Colonies? At that time, I decided that they were not always the best for all situations – especially in urban apiaries. Through the years, I have given slide deck presentations about dealing with large colonies. On many occasions, I have asked various beekeeping groups exactly how large of a colony did they ultimately want. The answers were vague and indecisive relative to the hypothetical question that I was asking. But my most aggressive effort, about thirty years ago, while visiting the USDA ARS Bee Breeding and Stock Center at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, was when I asked resident scientists why bee breeders always selected for bee strains that grew to huge populations. The answers to my question got no traction. There was no research interest in selecting for dynamically stable, smaller populations. Big colonies are always considered to be the best colonies. So, there it is. Managed bee colonies come in one size – extra-large.

Will I be able to change decades of management experience and protocol?

Okay, Jim, during the spring of 2022, you are going to keep bees in single deep or two deeps at the most. I must ask my beekeeper self; will I be able to withstand the pressure not to add more space to the brood nest when the colony outgrows the single deep? “Add more space.” That is what I would have done for the past forty-nine years. “They’re going to swarm.” How am I going to respond to my expected management behavior? I don’t know. Yes, I could make splits, but I don’t want more and more colonies. I don’t have enough equipment, time, or energy to produce splits as a management procedure to prevent swarms. Stand by.

To this point…

I have loved beekeeping for all these many years. Since I am not going to fade away from the craft, I hope that I can keep adapting by changing my ways with the bees. They will not be able to adapt to me, so I must do all the changing. For me, big heavy colonies are no longer practical. I fully realize that for many of you, big colonies and big crops are the way to go. It’s your time. Go for it.

In future articles, I will write more about bee life with smaller units and how I hope to still derive big (mental) rewards without all the physical labor that traditional beekeeping frequently requires. I do hope you stay with me through these discussions. My thoughts are not negative – just transitional.

Treasured memories

The December issue of Bee Culture Magazine has historically presented interviews with beekeeping authorities who are currently significant contributors to our unique industry. With the magazine editor’s approval, I have always elected to use my bit of space on this topic to acknowledge old friends who are not here anymore, but nonetheless, contributed significantly to our beekeeping passion.

Remembering Paul Jackson1, a good friend of beekeeping

Readers, this is not a formal biography for Paul Jackson. These are just some of my personal memories of a good, dependable friend who was in my life for many years. He’s been gone for six years, but I still remember.

Paul was the State Apiarist, Texas, essentially forever it seemed. He was there during the Tracheal Mite panic when thousands of hives were killed to control that new pest. That eradication plan didn’t work. Paul was left with the fallout from that failed effort. He was the State Apiarist during the arrival of the Africanzied honey bee into the U.S. Texas was ground-zero in the Africanzied honey bee issue for many years. You had to live it to understand that dark, uncertain time. Paul was quickly a “go-to” source of information for the rest of us across the country.

He was the Texas Apiarist when Varroa overtook that state. By then, he was well established as a practical beekeeping authority. Indeed, he was a steady hand for beekeepers through the biggest changes ever to occur in beekeeping. Yet, Paul was always a solid, practical beekeeper and dependable state employee. He was friendly to a fault, and he was a righteous person.

Uniquely, Paul was a bee smoker collector. He had the premier smoker collection in this country, and he would load it up and haul it to meetings and set it out on racks and stands designed for just that purpose. So, you didn’t have to go to Texas to see this collection; rather you only had to go to a meeting where Paul was speaking to view the collection. Even without the smoker collection, he always drove to meetings. Multiple times he drove all the way from Bryant, Texas to N.E. Ohio to my meetings. In retrospect, I don’t know if he really did not like flying or if he really just liked driving. Regardless, Paul always drove a white Texas State pickup to bee meetings.

Though I never saw any of them, he told me of his Coke Machine restoration projects. I don’t know his procedure for finding vintage Coke machines or how he restored them, but he did both. The pictures he showed were of beautifully restored Coke dispensing machines that he then sold “for big money.” I don’t know any other individuals who have done this unique work.

Paul and I were part of a group who visited Australia beekeepers. It was a grand trip that is still a highlight of my life. While there, he and I bought Australian Akrubra (cowboy) hats. We both got the Snowy River model. I still have my hat and wear it regularly. Within the greater travel group, Paul and I looked like a very small sheriff’s posse without horses. It was a good trip that yielded good memories (and quality hats).

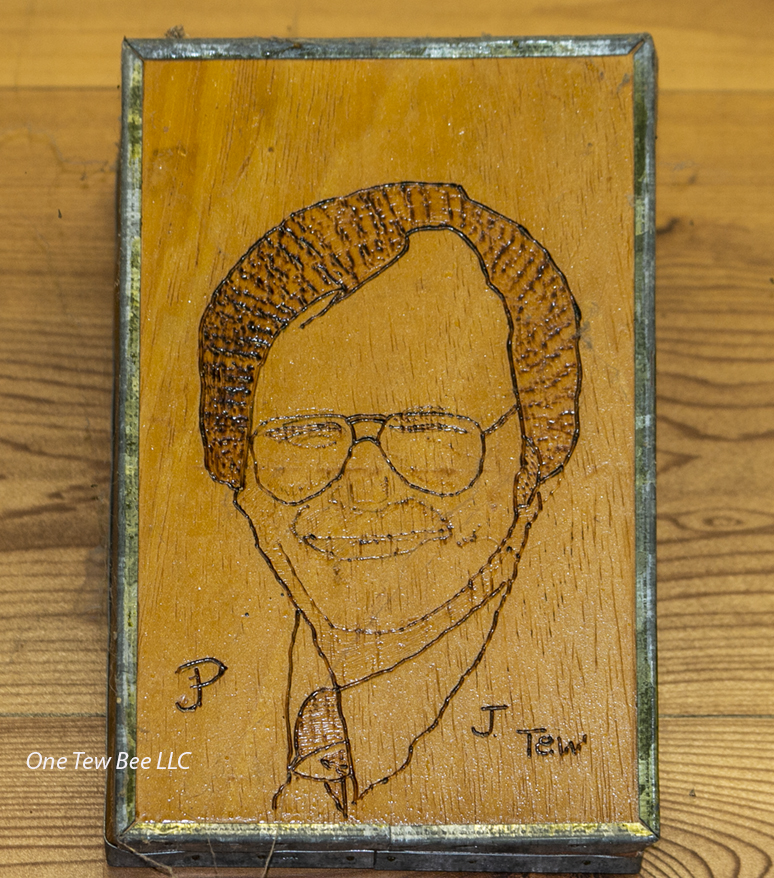

Though he lived in Texas, he had farmland in Arkansas. He knew farming. He knew all aspects of bees and beekeeping. He knew a good Coke machine when he saw it, and he never saw an old smoker that he did not want to own. A unique memento that I have from him is a woodburning likeness of me that he burned onto the back of a smoker bellows. It hangs on the wall in my shop. Paul, those who knew you do not forget, and we all miss you, old friend.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University and

One Tew Bee, LLC

tewbee2@gmail.com

http://www.onetew.com

1Paul Jackson Obituary – https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/bryan-tx/paul-jackson-6331908