Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Richard Wahl began learning beekeeping the hard way starting in 2010 with no mentor or club association and a swarm catch. He is now a self-sustainable hobby beekeeper since 2018, writing articles, giving lectures and teaching beginning honey bee husbandry and hive management.

Off the Wahl Beekeeping

New(ish) Beekeeper Column

Interests in Beekeeping (Where to Begin)

By: Richard Wahl

Some Interest or (The Just Curious)

It seems to me that there are three levels of interest among those who are curious about beekeeping, also called apiculture. For example, the person who asks what it is like to work with stinging insects, while I sell them a jar of honey, is not looking for the thirty minute lecture or one-hour presentation. They are simply seeking a quick summation before moving on to the next vendor. To that individual, I would respond: “Beekeeping is essentially animal husbandry with insects. Just as your pet pony or cat or dog requires food, shelter, water and regular care — like mucking out horse stalls, cleaning litter boxes, or regular outings — it’s the same with bees. They also need care, attention and vigilance for any pests and diseases that may arise. The key difference is that, instead of a mammal, you are attending to insects.” If we consider a colony of bees as a unified superorganism, functioning as a single cohesive unit, then the analogy to a pet makes more sense. Bees are often seen as one of the most intricate examples of a collective, cooperative society in nature.

A Greater Depth of Knowledge (The More Curious)

Some individuals go beyond surface level curiosity, delving deeper with more thoughtful and refined questions. These are people who are genuinely interested in what it takes to be a successful beekeeper, even if they have no intention of pursuing the hobby themselves. Their initial questions: “Have you been stung? Do you wear a bee suit? How many hives do you have?” Often evolve into more complex inquiries, such as: “How do bees make honey? How far will bees go to collect nectar? Do bees hibernate through the Winter? Does the queen collect honey?” These questions frequently spark even more in depth discussions about the fascinating world of beekeeping. As the questions deepen, it becomes clear that the person is not merely curious but has a genuine thirst for a more profound understanding of the intricacies of beekeeping, even though never intending to attempt the hobby. These discussions can last for tens of minutes or even run into hours when time permits.

The Beginner or (How Do I Start?)

Realizing there is much more to beekeeping than housing a group of insects in a box, collecting honey and letting the insects fend for themselves is the first step in becoming a proficient beekeeper. Before jumping into the art of apiculture, or hive organization and beekeeping, one should read books and/or articles on the subject to become familiar with bee biology, behaviors and hive management. Some of the more prolific authors on beginning beekeeping include Kim Flottum, Michael Bush, Sue Hubbell and Thomas Seeley as well as many others. To get deeper into honey bee biology and the art of beekeeping, search out books by Dewey Caron, Marla Spivak, A. I. Root (Bee Culture), Richard Jones and Sharon Sweeney-Lynch to name but a few. Look for state and local beekeeping associations that offer beginner courses, recurring conferences and club memberships. The greater the depth of knowledge, anticipation of the challenges and the pitfalls of beekeeping in advance, the better the chance for beginning beekeeper success. Taking an entry level class on beginner beekeeping is also a good idea. Many clubs and associations offer classes, both online and in person. Courses will often cover necessary equipment and seasonal tasks as well as bee health and hive management. The more hands on and in person mentoring the class offers, the greater the depth of knowledge the beginner gains. Be sure to check local regulations, zoning and any permit requirements or mandates for hive inspections in your area. This is particularly important if you live in a more urban area. There may also be honey sales restrictions or requirements which will usually fall under state small cottage industry rules. It is best to know about any of these legalities before getting too far into the business side of beekeeping. Joining a local club or association can provide valuable insight into any of these unforeseen requirements.

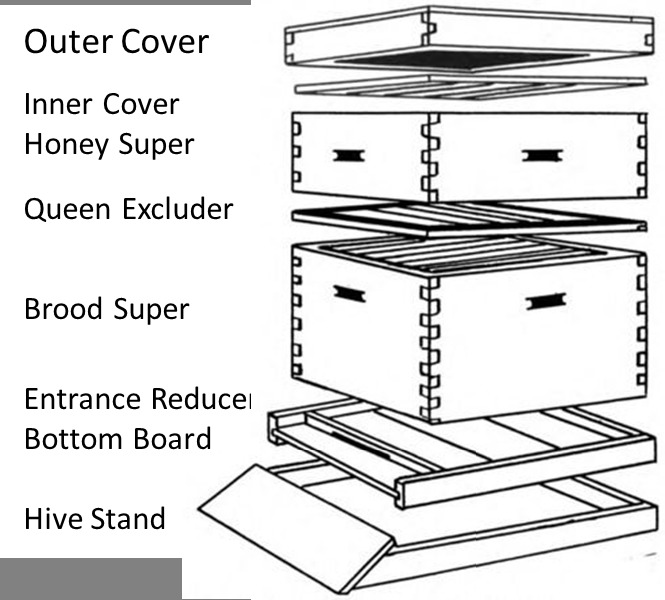

Beekeeping Equipment

The next step is to choose your beekeeping setup. The most commonly used type of hive is the Langstroth hive which is a group of eight or ten frame boxes stacked atop each other. Although I work with ten frame deeps, if I had it to do over, I would select eight frame supers as the weight of a ten frame deep is considerable more than an eight frame super when full. In bee vernacular, the largest box that holds eight or ten frames for purposes of brood rearing is called a deep or a super. They are 9⅝ inches tall. Currently boards designated as ten inches wide in the lumber industry are in reality only 9¼ inches wide. The DIY craftsman would need to purchase a designated 12 inch board (normally cut down to 11¼ inches by the lumber industry) and cut it down to the required 9⅝ inches tall needed to house deep frames if constructing one’s own hive boxes or nucs (nucleus hives). Another method beekeepers promote is to use three medium supers for brood rearing which are each 6⅝ inches tall. Using medium supers for both brood rearing and honey supers allows them to be interchangeable. As age starts to take its toll I am considering slowly cutting down my deep boxes to mediums mitigating some of the weight problem of lifting heavy deeps. Another less commonly used hive type is the top-bar hive which lays all the frames out in a horizontal box with dividers such that the hive size can be increased or decreased horizontally as needed. Full Langstroth style beginner hive kits including bottom board, deeps or mediums with frames, an inner and outer cover, can be purchased as kits from numerous beekeeping equipment suppliers. The Langstroth style hive is the usual starting point for beginning beekeepers.

The next consideration is a beekeeping suit and gloves. The ventilated suits will be more comfortable on hot Summer days, but of course come at a greater cost. A face veil of some sort is nearly always a necessity as bees have a tendency to attempt to attack the face around the eyes if defensive or agitated. Although I generally only use a ventilated jacket with veil, I would recommend the full suit and veil for a beginner until becoming familiar with your bee’s temperament. As one becomes more familiar with hive manipulations and inspections, your comfort level while working with your bees will dictate the level of suit protection you need. In my first years of beekeeping I suspect my nervousness could be sensed by the bees which seemed to become less aggressive as I became calmer and more comfortable with bees as the years passed. When it comes to gloves the bees seem less bothered by goatskin gloves as opposed to other types of leather. This is just a personal opinion and not based on any research I have read or equipment seller advertising. In addition to the suit and gloves, getting and learning to use a good smoker will be an asset. I suggest the taller style smoker which provides more fuel space and lessons the chance of a burn when initially lit as the taller smoker raises the starter flame farther above the baffle when the beekeeper lights the smoker. A hive tool, which is no more than a flattened pry bar tool, will also be needed to pry and lift frames out of supers. A set of two or three different sized pry bars can often be found at big box or hardware stores for a comparable price to those sold in beekeeping supply catalogs. The last item recommended for the beginner is a bee brush. These can be used to gently brush bees off comb when inspecting or to remove bees from capped honey comb when collecting that first honey resource. There are many other nice to have items in the bee catalogs that can enhance the beekeeping experience but they are not necessary to become successful. If the new beekeeper sticks to the basics as listed above they can do just fine as a beginner.

Selection of Bees

The next area of concern is to choose your bees and the source from which they come. The particular sub-species of bee is not nearly as important as getting bees from a local beekeeper or supplier. Bees that are adapted to local conditions have a better tendency to thrive in the area of origin rather than those that need to adapt having come from other distant out of state locations. My first colony of bees was the result of a swarm catch so I cannot claim their sub-specie origin. During my first years of beekeeping I did subsequently purchase Italian, Buckfast and Saskatraz packages, but with one to six swarm catches every year, I do not know what my most prevalent sub-species is. My queens range from nearly pure yellow through striped to nearly full black. If the beginning beekeeper is purchasing a starter nuc it should contain at least two if not three frames of capped brood with an additional frame filled out with pollen/honey as a food source and possibly one empty frame, along with that brood’s queen. The nuc purchase gives the new beekeeper about a month head start over the purchase of a package. Packages are normally sold in three pound two sided screened boxes with a quart container of sugar syrup and an internal smaller screened box containing a queen and a few workers to attend her. Placing a package in a new hive requires the bees to draw out new comb and start the hive from scratch whereas the nuc already has eggs, larva and capped brood along with four or five frames of drawn comb providing a head start on a package.

Apiary Layout

How to set up your apiary is the next decision the new beekeeper needs to make. Hives should be placed in a sunny location with the porch opening to the south or east to take advantage of the morning rising sun. They should also be situated such that a north and west windbreak can be placed behind them for cold Winter wind protection. High pedestrian traffic areas should be avoided or surround hives by a six to eight foot high fence so bees need to fly upward before continuing on a horizontal journey to their nectar sources. A three to four foot space around hives provides adequate work space, especially behind the hives where the beekeeper will stand for most inspection and honey frame removal work. The farther apart hives can be set with different colorations and orientations, the less likely for drift from one hive to another and the less likely the passing of disease or pests from one hive to the next.

Installation of a Package or Nuc

Once the previous decisions are made it is time to install the bees in the hive which will normally occur in the very late April or early May timeframe in our area of SE Michigan. Rather than rudely dumping a package onto new frames a second empty deep box can be set over the first, the syrup can removed and the package set on its side to allow the bees to migrate into the hive frames below. The queen can be placed between two frames where she is cared for through the screen by her bee sisters and can be released once the bees have settled in. When all the bees have moved onto frames below the empty upper super can be removed. After only twenty to thirty minutes most of the package bees will have crawled onto the frames. Any bees remaining in the package box can be shook out into the hive super or nuc that will become the bee’s new home. Check in about a week to see that the bees are drawing comb, the queen is laying and the bees are storing pollen and nectar. A one to one sugar syrup and pollen patty supplement for a new package will help get them off to a good start. If a nuc package was purchased the nuc frames can be placed in the receiving deep with the remaining space filled in with empty foundation frames. Even if waxed frames were purchased, coating new frame foundation with a thin layer of beeswax will entice bees to draw out new comb a bit sooner.

Hive Inspections

Once the bees are established in a hive the inspection routine by the beekeeper begins. How often to inspect a hive, is one of those conundrums that new beekeepers face. Checking a hive once a week will help the beekeeper to become familiar with the ebbs and flows of the queen and the bees. Check for signs of the queen’s presence (eggs and brood), that the bees are building comb and storing nectar and pollen and look for pests, diseases, or signs of overcrowding which can lead to swarming. As familiarity with hive management increases checks can be spaced farther apart. If I know there is a queen laying eggs, larva being cared for and capped brood with bees emerging, I may not do a deep hive inspection of all frames for six or eight weeks. At those times I check to see that there is still room remaining in the honey supers and as long as bees are seen bringing in pollen I assume the hive is functioning in a good manner. As supers reach 85% to 90% filled I will add additional supers. If the filling of honey supers seem to stagnate it may be time to do a deeper inspection. With a bit of experience the beekeeper can assess a lot by watching the comings and goings of bees on the landing porch and how frames are being filled in the honey supers. Less frequent inspections seem to be the norm as beekeepers gain more experience. It is estimated that a full frame inspection of a hive sets that hive back one or two days as the bees reestablish their activities and networks after a full inspection. Be gentle and avoid excessive disturbance during inspections to reduce stress on the colony. Continuing to feed one to one sugar syrup and pollen patties if pollen is scarce is particularly important if there is a late Spring or early Summer dearth with the flowers providing little or no nectar and pollen.

If the bees were purchased as a package and had to build comb and store nectar and pollen the beekeeper would be advised not to take any honey from them in their first year. The stores the bees may have accumulated will be needed to survive their first Winter. This will hold true the farther north that the hives are located. On the other hand, a purchased nuc may have acquired sufficient stores such that some honey may be taken by the beekeeper later in the Fall. A lot will depend on the Summer rains which determine nectar and pollen availability. I have seen Summers with dearths when no pollen or nectar was available and very little honey was made. Other Summers had biweekly rains which allowed bees to collect nectar throughout the season and I was able to take honey from first year early swarm catch hives. Each Summer and year will be different. Once the honey is capped by the bees it means it has fully ripened to the less than 18% water content and can be harvested. A small amount of 5% to 10% uncapped honey existing on a frame with mostly capped honey will not degrade the quality of the honey. If by shaking a frame nectar drips out, it is not ready. Honey that is near ready to be capped will not drip out of the shaken comb on a frame.

Other Considerations

Dealing with pests and diseases gets into an entirely different area that I will leave for a future article. Likewise winterizing a hive calls for additional actions by the beekeeper. I covered Winter preparations in the November 2023 issue of Bee Culture magazine titled “Winter is Almost Upon Us”. In all instances beekeeping requires patience and due diligence. Apiculture is an avocation that takes time to master and it is normal to face some challenges along the way. The objective should be to enjoy the learning process and the journey with your bees. Start small and learn the basics before expanding too fast. Respect your bees and the society they have created and you can become a self-sustainable beekeeper in a few short years.