When Considering the Data

D. Tracy Farone

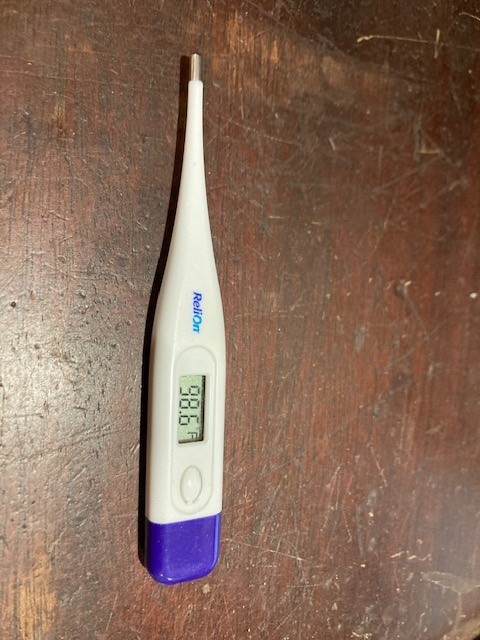

If I asked you, “What is normal human body temperature?”, what would be your answer? Most people (and maybe even some health professionals) would say 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit (or 37 degrees Celsius). You may have solidly believed this your whole life. However, this data point is based on one, single, now highly disputed study performed by a German physician, Dr. Wunderlich, in the mid-1800s, taking axillary (armpit) temps with a questionable thermometer (1,2,3). In psychology, they refer to this as the “illusory truth effect” or if something “is repeated enough times, the information may be perceived to be true even if sources are not credible.”(4).

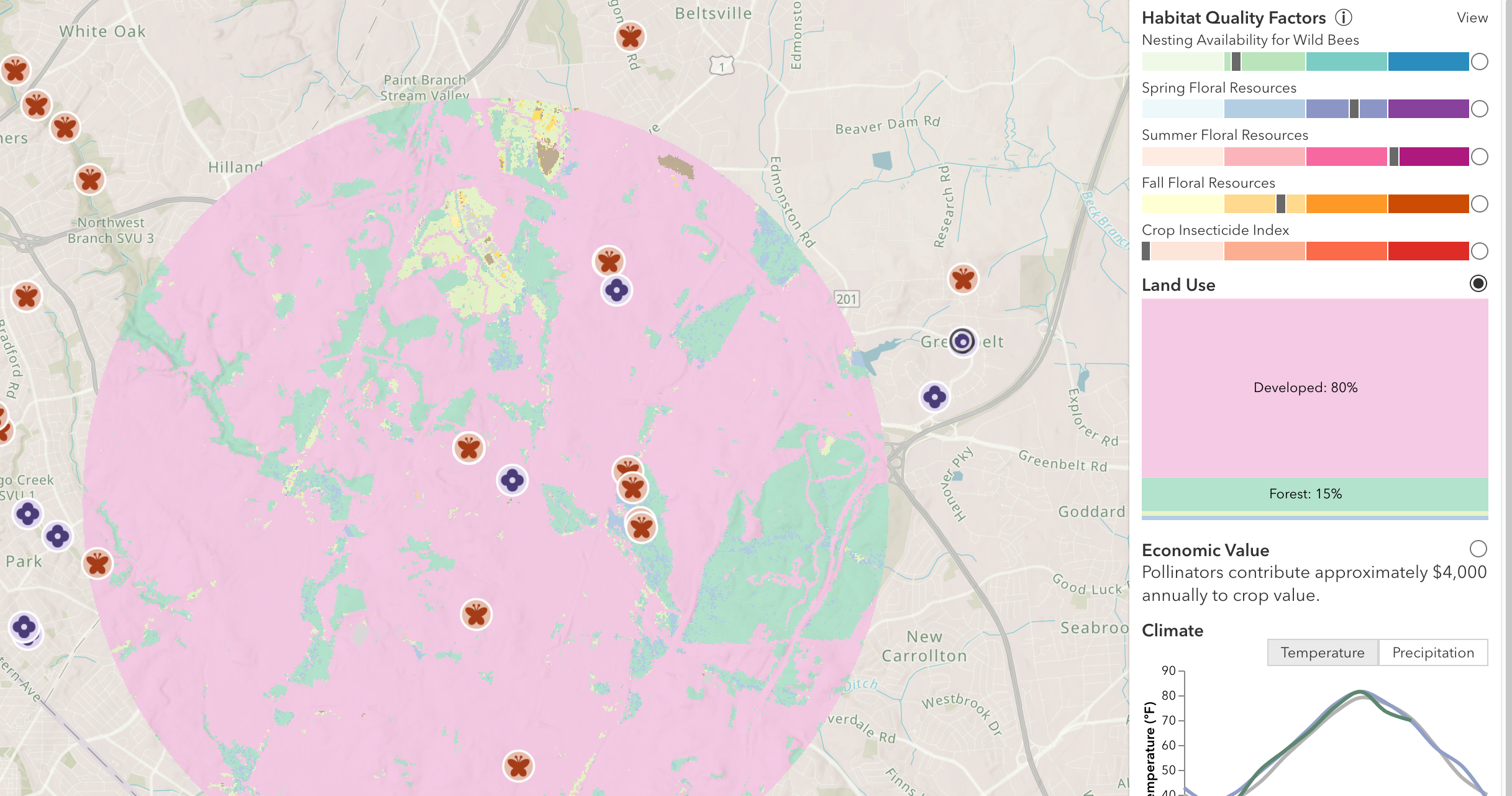

As a veterinarian for over 20 years now, I always wondered about this single, 98.6, human number because, as vets, we were not taught single values for normal animal body temperatures but ranges of normal. For example, normal horse temps are from about 99-101.5F with anything over 102 raising our eyebrows. Cattle average about 101.5 with anything over 103 considered to be a fever. Cats and dogs fall into a 99.5-102.5 range, but with freaked out cats coming into a clinic, I’m not surprised by a 103 or even higher given the situation. As thermoregulators, even our honey bees are capable of a wide range of “body” temperatures within their hives. Brood and winter core clusters temps range from 90-95°F, with outer parts of the winter cluster being much cooler, with ranges from 81°F to the mid-40s (5).

Body temperature ranges make sense because body temperature is a variable that can vary and change within a normal homeostatic range depending on host and environmental characteristics. Body temperature in individual animals and humans can be affected by many things, including age, height, weight, activity, gender, stage in reproductive cycles, pregnancy, and the time of day.

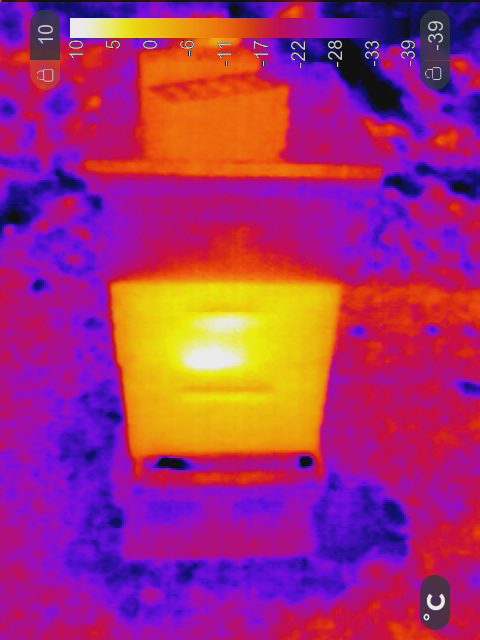

The accuracy of measuring this variable also depends on the use of proper instrumentation and methodology in our data collection. With body temperature, internal testing methods, rectal and oral thermometers, are the most accurate for measuring body temperature (we tend to use rectal thermometers in young children and animals and oral in older children and adults). External, non- contact thermometers, which are now popular due to convenience and perceived safety, are less accurate. We also need to be sure our method is correct. Remember mom saying, “be sure to put it under your tongue”? She was right. Improper placement, inadequate testing time, and being outside, exercising, eating or drinking before using an oral thermometer will affect its accuracy (6).

The current scientific consensus involving many more recent studies on human body temperature, (which managed some main stream press coverage in pre-pandemic 2019), now considers humans to have a normal range of body temperature somewhere between 96-99.5°F, with an average of about 97.7°F. Most doctors agree that 100.4° or above is definitely a fever (personally, I’m wiped out by anything over 99°F). Does this surprise you?

I present to you this “temperature check” to illustrate that in any science, it is very important to not just know the “facts” or data presented, but to be able to fully ascertain the what, how, when, where and why in the generation of the information. Once information is elevated to “facts”, this information becomes what we based our beliefs and actions on. It is also important to accept that for many things there may not be a single, yes or no answer but a range of “correct” answers affected by many variables. Much of what I presented above is analogous to how we should evaluate data used in beekeeping decision making.

Recently, I was asked to speak at a local beekeeping club on small hive beetles. I enjoy the opportunity to speak with beekeepers because I try to not be the only talking head in the room and give the group the opportunity to share their thoughts as well. It gives me great food for thought when listening to other people’s perspectives and you never know what others are thinking unless you ask. At this particular meeting, I was asked, “Are (all) treatments for Varroa mites effective in treating for hive beetles?… Yes or no?!!”

The short answer to this question is, “No.”

The label is the law. Miticides for use on honey bees are not formulated, intended, or labeled to kill an insect like small hive beetles. But I believe this bee may have been wanting me to say, “yes”, because we know that many chemicals (insecticides, pesticides, fungicides, herbicides, miticides) can potentially have negative, even if sub-clinical, effects on insects, like our bees, so why not small hive beetles? Maybe we could assume, believe, that there is some effect on hive beetles, too…? I suppose if you’d put a hive beetle or just about any other living creature into a vat of amitraz, oxalic acid, or thymol for a time, it would not be promotional to their good health, but this of course, would not be anything we would do in practicality or be backed by any scientific study that I am aware.

However, after the meeting, I got to thinking. While the technical answer to the posed question is, “No”, the IPM answer to the question is – Yes! If beekeepers are properly using an effective Varroa treatment program and controlling mites in their hives, they are doing one of the most important things beekeepers can do to keep their hives strong with effective immunity. And keeping strong, healthy hives is one of the best preventions in fighting small hive beetle infestations. So, yes….the range of “correct” answers depends on your perspective.

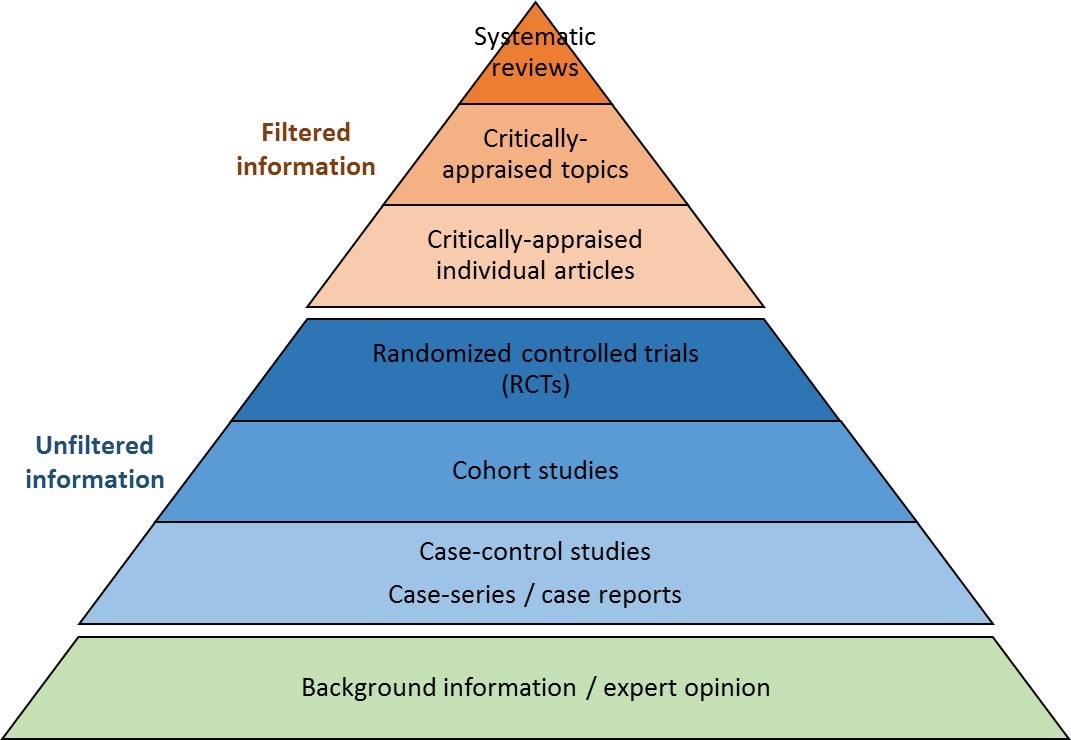

Everyone likes to be correct…to know what they are talking about. But science and beekeeping has continued to teach me to be diligent in considering questions and answers, the credibility of data resources, and to understand that there are many variables going on at the same time, particularly in the field with wild animals such as honey bees. Additionally, if one investigates just about any topic beyond a typical “Google” search, you’ll shortly find that even for “experts” in a particular field, we’re honestly just a few questions away from, I don’t know….much is unknown… the data is changing… or more research is needed before we can jump to any one-size-fits-all conclusion.

References

1.https://health.clevelandclinic.org/body-temperature-what-is-and-isnt-normal/ Accessed 12/09/2021.

2.https://wexnermedical.osu.edu/blog/new-normal-body-temperature Accessed 12/09/2021.

3.https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/time-to-redefine-normal-body-temperature-2020031319173 Accessed 12/09/2021.

4.https://www.psychologicalscience.org/news/repeating-misinformation-doesnt-make-it-true-but-does-make-it-more-likely-to-be-believed.html Accessed 12/09/2021.

5.https://www.beepods.com/honey-bees-survive-winter-regulating-temperature-cluster/ Accessed 12/09/2021.

6.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK263242/#S23 Accessed 12/09/2021.

Source of data pyramid: https://latrobe.libguides.com/ebp/study-design Accessed 12/10/2021.

Farone, Tracy S., Registered Medicinal Products for Use in Honey Bees in the United States and Canada, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice, Volume 37, Issue 3, 2021,Pages 451-465.