By: Bill Miller

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 2017 issue of BEEKeeping Your First Three Years

If your attorney says beekeeping is ok, get it in writing!

While most non-beekeepers think having a neighborhood beekeeper is amusing and/or harmless, our neighbor initiated a lawsuit intended to force my wife and I to remove bees from our property. What follows is the story of that lawsuit from our point of view. Along the way, we made many observations that need to be shared with the rest of the beekeeping community, especially those who are considering starting beekeeping in a suburban neighborhood.

I am not an attorney myself. Based on what happened to us, I highly recommend you talk with your attorney before you start beekeeping in a suburban/urban neighborhood. Assume someone will try to sue you to force removal of the bees – you need to know if he can fabricate a case. Those folks who will want to sue you are out there. If one of them can get a case going, then you might just get a certified letter inviting you to spend many thousands of dollars on attorney’s fees.

Let’s start at the beginning of our case. When we first moved to Dothan, Alabama in 2006, we knew we wanted to keep bees on our property, and so informed our real estate agent. We also said we did not want to live in a place with covenants, and preferred a mostly rural location. We found what looked like a suitable house – 3.2 acres with a hayfield for one “neighbor” and a cow pasture for another “neighbor”. There was a house behind the one we were considering, it had a large open pole barn where a farm tractor was stored. When we asked about covenants, we were told there were none. We bought the house; and as expected the deed did not reference any covenants.

We moved in, met our neighbors in the house behind ours and told them of our proposed beekeeping on the property. They didn’t voice any concerns then. The next Spring (2007), I set up hives (at first unoccupied) and told my neighbors that if they had any objections let me know before I installed bees in the hives. Again, the neighbors didn’t object. I installed packages in the hives, and again no comments from the neighbor.

That’s things stood until late that Summer, until one day my neighbor drove over in his farm tractor (incidentally running over my wife’s garden in the process), and told us that beekeeping was forbidden on the property per the covenants. We called the attorney who handled the closing to find out what was going on, and on double checking learned that we had bought in a development consisting of 2 houses, there were covenants on the property, and the covenants forbade the keeping of “animals” other than dogs and cats (I’m paraphrasing a bit here). The attorney who handled the closing was properly embarrassed at his missing the covenants when he prepared the house settlement package. His advice was that for the moment we should sit tight and see if anything further developed.

Let’s get back to the event history. For several years, the closing attorney’s advice of “Sit tight and see if anything develops” was valid. I maintained the colonies, and no objections were voiced. When the bees swarmed into one of my neighbor’s trees, my wife got a phone call from my neighbor saying “Please tell Bill his bees are trying to leave home, and they are camped in the tree by our carport”. That is the kind of reaction to a swarm I would expect from someone who lives next to an apiary. Of course, I retrieved the swarm. Also, the neighbor came over one day when I was working the bees and I showed him what goes on in a colony. He seemed interested. Everything looked to be working out well, and I didn’t hear any more complaints. The bees and their hives were accepted (or so I thought). By the way, I never heard about another swarm on my neighbor’s property, or for that matter heard any other complaints about alleged bee misbehavior.

Lesson Learned:

If your attorney tells you something such as beekeeping is legal to do, get a letter from him stating his opinion. In our case, the attorney who handles our next house closing will be asked to include a letter stating that the property is legally suitable for beekeeping without further restrictions (or these are the applicable legal restrictions). Also, document that you asked your neighbors about beekeeping and they were OK with it.

Also during this period, the attorney who handled our property closing had a stroke and was forced to retire.

In 2014, I received a letter from an attorney stating that he had been retained by my neighbor to file suit to force me to remove my beehives as a covenant violation. The letter claimed my bees were a nuisance to my neighbors and so they had to go. They also claimed my beehive color scheme (FYI, they have yellow boxes with green outer covers and bottom boards) were nontraditional and garish. This letter was a courtesy to let me act before the suit was actually filed.

You can’t let a letter like this go unanswered. I was fortunately able to locate an attorney who also kept bees in a neighborhood, and the correspondence between the attorneys began. My neighbor couldn’t produce backup information for claiming my bees were a nuisance. Slowly the real issue began to surface; my neighbor didn’t like having to look at beehives when he looked across my property. He claimed that when I taught my beekeeping classes I advocated keeping beehives hidden from view, and had even written a pamphlet advocating keeping beehives hidden. The neighbor further accused me of being a hypocrite for ignoring my own advice. Having never written such a pamphlet (I do not advocate keeping beehives hidden from view), I told my attorney to ask my neighbor to produce the pamphlet. Of course, he couldn’t produce a pamphlet, and his attorney lost interest in the case. No suit was filed. I had spent $2000 in attorney’s fees, but our beekeeping on our property was safe (at least for the moment).

In April, 2016 my wife and I got a certified letter stating my neighbor had filed a lawsuit against us to force me to remove the bees from my property. He had found a new attorney; this one specialized in being a trial attorney for plaintiffs. All the same claims were made that my beekeeping was a nuisance that prevented my neighbors from using their property, my property was overrun with too many hives, and an additional claim that we were running a beekeeping business contrary to another part of the covenant. My neighbor wanted my beekeeping business profits, and subpoenaed copies of my tax returns to ensure he was getting the full amount due.

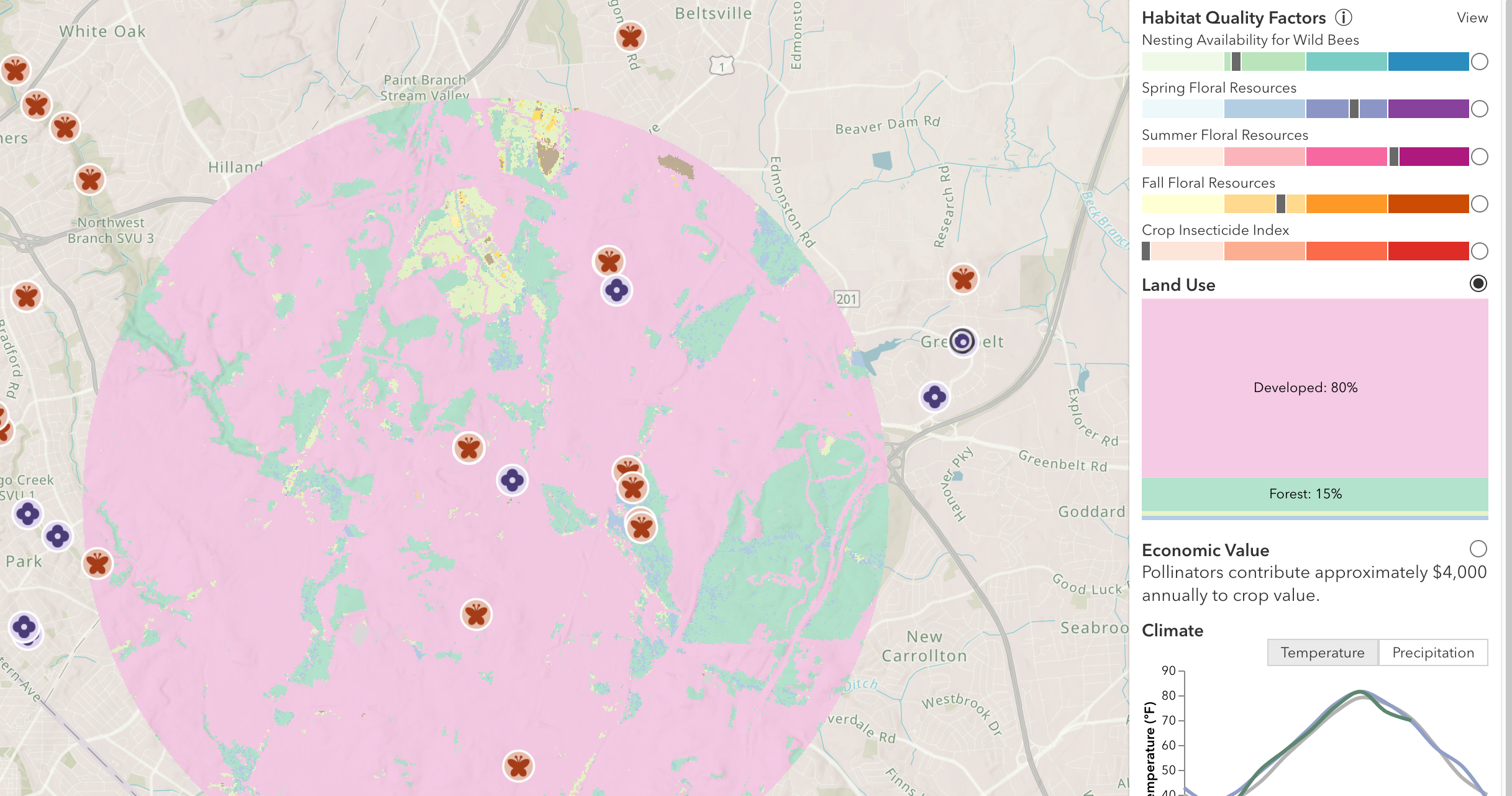

I retained the same attorney I had before, and set about answering the claims made in the suit. The bees were a nuisance? Dothan has “Good Neighbor Guidelines” giving the expectations for beekeeping. I got our state bee inspector, our local extension agent (he does keep bees), and an Alabama Master Beekeeper to look over my beekeeping. They all wrote affidavits saying my beekeeping was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines. The colonies were registered, peaceful, an appropriate distance from property lines, the equipment was in good condition, and the number of colonies was appropriate for the 3.2 acres we own. We run a beekeeping business? We provided copies of our tax returns (with the information not related to beekeeping redacted by our attorney) along with a letter from our accountant stating that since our “business” lost money, we were actually hobby beekeepers. Our bees interfere with our neighbor’s use of his property? I took pictures of our neighbors using their property with no apparent concern for our bees.

Lesson Learned: The real issue in a lawsuit can be remarkably petty. In this case my neighbor wanted us to run our property to meet his desires, and was using the covenants to try to force his desires on us. Also, plaintiff’s attorneys are paid to win cases for their clients. They are not paid to confirm the allegations their clients make in complaints are justified.

As before, the real issue had nothing to do with bees. My neighbor thought beehives on my property spoiled his view when he looked out across his yard into ours. He also didn’t want to have to see beehives when he drove down the road.

The neighbor then submitted a proposed settlement that we rejected as unacceptable, and we submitted a proposed settlement that the neighbor rejected. The neighbor’s attorney then filed for summary judgement against us, and our attorney filed a counter. Of course, all this time the attorney bills are adding up. Finally came the day of the summary judgement hearing. The plaintiff’s attorney argued that since the bees were biologically “animals”, they were forbidden by the covenants.

Our attorney argued that using the biological definition of “animal” was inappropriately broad, and the plaintiff’s attorney’s interpretation would have meant people couldn’t live on the property either. He also argued that the bees had been there for many years, and the statute of limitations for bringing up the issue was long expired. Summary judgement in favor of the plaintiff was denied, and the judge ordered us to mediate the issue.

A mediator was appointed, and he stated that he didn’t know anything about beekeeping. I tried my best to educate him in the few minutes we had with him before mediation started, but some of his remarks told me he had no feeling for the emotional attachment we have for our bees, or the risks involved in moving a hive any time we feel like it. By the way, the mediator also charges for his time.

In mediation, the plaintiffs and the defendants (my wife and I were the defendants) are placed in different rooms, and the mediator shuttles between them with the proposals, counterproposals, and a very high pressure sales pitch for all these proposals. In the end, we accepted a proposal that amounted to an 85% win for my neighbor. I have to move some hives, but I do get to do it in the Spring when moving bees is feasible. We will be allowed to keep bees on our property, but we will be more restricted in colony numbers and locations than those allowed in the Good Neighbor Guidelines.

Had we rejected the mediation solution and instead gone to a full-blown trial, I am 90% certain we would have won (In the legal business, nothing is certain until the judge bangs his gavel for the last time). So why did we accept an 85% loss? Two reasons apply: 1) Money – going to trial would have probably cost at least another $10,000. 2) I became convinced that my neighbor was the irrational type who would have done anything to “enforce” his view of how we should manage our property; this includes sneaking over onto our property in the evening and shooting wasp spray into my hives.

I do treasure a comment our attorney made to my wife during mediation: “Now don’t do anything like putting out old toilets with flowers planted in the bowls to get him (our neighbor) riled up”.

So now the case is essentially resolved (the attorneys still have some paperwork to finish up). We can’t sue our original closing attorney for malpractice on the grounds he missed the covenants; that attorney is out of business. We are going to make a claim on the title insurance as the property was not properly represented on the deed.

Those are our personal actions. On a State level, I will be working through the Alabama Beekeepers Association to get state law to say beekeeping is legal unless specifically banned by name by some applicable legal instrument. Some covenants do say “No beekeeping”; I have no arguments with that. I just don’t want someone to be able to use an overly broad interpretation of a term like “No animals” to stick his nose into other people’s affairs. As you can see from my story, once that nose is stuck into your affairs, it’s very difficult to get it out.

I will also be working to get aversion Dothan’s Good Neighbor Guidelines made into Alabama law, with the provision that people who follow the Guidelines will be immune from beekeeping lawsuits. My understanding is that West Virginia and Virginia already have such laws; I encourage all State beekeeping associations to do the same.

With the increased interest is suburban beekeeping, this sort of lawsuit will become more common; our judge said he had several in his in-basket. For the State beekeeping associations, the task is to stop these lawsuits before they start. For the average beekeeper (and especially a prospective beekeeper in a suburban area), it might be a good time to have a chat with your attorney.