By: Andrew Connor

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2019 issue of BEEKeeping Your First Three Years

I spend my days as a mental health worker-helping people with people problems-so the last thing I expected at my day job was helping a coworker with a bee problem. One morning, she showed me a photo: A black and yellow blur. She said honey bees were invading her kitchen.

When I arrived at her home in the heart of southwestern Michigan’s blueberry country, I expected to find a hive of honey bees in her kitchen wall, filled with the best honey this side of Lake Michigan. I expected to find honey bees.

Before I could get too close, I felt a sharp pain in my arm that hurt more than a normal bee sting. Then I felt several more. I checked the new bumps on my arm that were already getting red then examined the critter that had fallen to the ground after I swatted it. Six legs and shiny black skin. The creature that was invading my coworker’s kitchen and tried to kill me wasn’t a bee at all. It was a yellow jacket.

After I iced down my wound, the only thing left to do was educate my coworker. Not all black and yellow insects are honey bees.

What Exactly is a Bee?

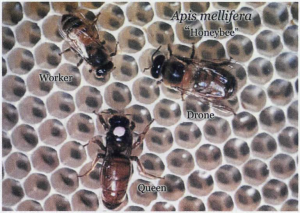

The scientific name of a honey bee is Apis mellifera, but that doesn’t tell us too much. Apis means “bee” in Latin, and mellifera means “honey-bearing”, but being that specific doesn’t help us distinguish between different insects. We have to go broader.

In the broadest classification parameters popularized by Linnaeus, bees are classified into the Animal Kingdom. Because they have an exoskeleton and a segmented body, they fit in the Arthropoda Phylum. Spiders also fit in the Arthropoda Phylum, but since bees have two fewer legs than spiders, bees belong in the Insecta Class. From there, the requirements for classification gets more complicated. There are a lot of insects in the world, and only a few of them are bees.

To understand more about bees, let’s look at the Hymenoptera Order where all bees fit.

Hymenoptera

Translated from Latin, “-ptera” means “wings” (like pterodactyls) and “hymen” means “membrane”. As all members of Hymenoptera have membranous wings, this name is fitting. But wings aren’t the only similarity Hymenoptera share.

Most bee and wasp species are solitary, meaning they live and work alone, but honey bees are different. Honey bees in particular are considered one of the most socially developed insects in the world.

Social insects live in a colony of fellow insects of the same species. They each have certain jobs and responsibilities and are dependent upon each member of their colony to survive. While this perfectly describes the behavior of honey bees, there are other insects who are considered social.

Ants usually live in a complex social colony with one or more breeding queens. They are industrious eusocial insects, meaning that a single to several reproductive individuals live within the group of non-reproductive daughters and sisters. The membranous wings from the Hymenoptera name refer to the reproductive ants whose wings aid in the formation of mating swarms.

Paper wasp ‘queen’ generates heat with her flight muscles to warm the eggs and larvae in a new nest made of chewed wood.

Wasps and hornets are also eusocial, and as we learned in my earlier example, they closely resemble bees. Superficially, wasps have four membranous wings like honey bees, but they have significantly fewer body hairs than most bee species-their shiny, metal-like abdomen is a dead giveaway. There are several subtle differences in their appearance, but the main difference between wasps and honey bees is their behavior.

Unlike honey bees, wasps are carnivorous. In addition to sweet food like fruit ripening by a kitchen window, wasps can often be found feeding on other insects. The specialized mouthparts of yellow jacket wasps allow them to cut through the bodies of their prey, and their biology allows them to digest anima l proteins. In contrast, the mouthparts and digestive enzymes of the honey bee allows it-a natural vegetarian-to eat pollen and honey. Yellow jackets tend to be more violent; their lance-like stinger differs from the honey bee’s barbed stinger and is smooth, which allows yellow jackets to sting repeatedly.

Many wasps are found in sheltered areas where they’ve built their nest from wooden material they’ve chewed into a pulp-like paste. While this behavior is also evident in some bee species, the honey bee does not.

Now that we know what bees are not, let’s talk about the honey bee. Although there are a lot of kinds of bees, the honey bee is the one we like.

The Honey Bee

Honey bees are important pollinators of flowers and crops, and everything about them helps them earn this title. The plumose hairs all over their body are branched, allowing them to capture pollen efficiently. Their antenna cleaners on their legs help them pack pollen into their corbiculae, the pollen basket located on their hind legs of worker bees, to store until they return to their hive to deposit the forage.

Honey bees live in cavities found in nature or in manmade hives. In the wild, they typically live in trees, logs, or any structure that provides a mostly closed, dark, dry place to nest.

The color of honey bees appears less bright compared to other insects like the yellow jacket or bumblebee.

Like all social insects, inside of the nest of honey bees are three castes: The female worker, the male drone, and the single reproductive female queen.

The Worker

The Worker

Workers tend to be the most popular caste of bees. If you’ve seen a honey bee foraging on flowers in your garden, that was a worker bee. If you’ve seen a honey bee sealing leaks in a hive with propolis, building beeswax, processing honey or curing pollen, that was a worker bee too. Worker bees have a lot of jobs.

They’re even in charge of defense; female honey bees are the only members in the bee species who can sting. Yellow jackets, as we learned, can sting multiple times, but workers can only sting once until it dies, giving its life to protect the colony.

The Drone

In the area where I live, drones do not usually live into the Winter. Once foraging season is over, drones will be prohibited from entering the hive by worker bees who will do whatever it takes to reserve resources for the coming Winter. In some cases, especially when the colony experiences a shortage of nutrition, drones are also excluded from the hive, even in the Spring. During periods of nutritional stress, the workers first eliminate drone eggs, then larvae and pupae. In extreme food shortages, the workers may eliminate mature drones until eventually eliminating worker eggs and larvae as well.

A healthy hive has no biological need for drones outside of the mating season. While drones don’t have as many responsibilities as the worker, their primary role of mating is just as important to the survival of the colony.

Adult drones spend every afternoon searching for an unmated queen.

Queen with Multicolored Workers – Queen producing workers with different color patterns, perhaps reflecting different drone fathers and their superfamilies.

The Queen

The queen in the hive is not a monarch in human terms, but she is responsible for the entire colony. In addition to laying eggs after she’s mated with several drones, she delegates tasks to the worker bees through pheromones, or communication chemicals. Her pheromones are the social glue of the colony, helping the worker bees to function as a single (large) family.

She is larger than the other castes, most notably in her abdomen where her ovaries are stored.

When newly emerged from her brood stage, she is called a virgin, but when she mates with one of several bazillion (up to 60 or so) drones during the mating season, she is considered mated.

Closing Thoughts

Knowing all this, it’s hard to see why my coworker mistook a yellow jacket with a bee, one of nature’s most fun insects. They’re so fun that it would be hard to talk about how fun they are in one article. In the second part of this article, 1’11 talk about the different bee species, honey bee races, and special groups of honey bees any beekeeper should know about.