By: Peter Sieling

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of BEEKeeping Your First Three Years

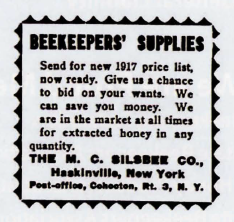

In 1917, an ad appeared in Gleanings in Bee Culture for the M.C. Silsbee Company of Haskinville, NY, a firm that manufactured beehives, rendered beeswax, and bought and sold honey. Within a year the ad disappeared. Haskinville is a ten minute drive, so Taeciaed to solve the Mystery of the Disappearing Bee Hive Factory. The story that unfolded must have been the scandal of the century.

We first met the Silsbee’s in 1890 when Bee Culture’s roving reporter, John Martin, AKA the Rambler, rambled through Steuben County, New York. He described it as “a land of forests and glens, perfect for bands of brigands”. To reach Haskinville, the Rambler traveled up Neil’s Creek Rd. which winds through a gorge. Residents live in perpetual twilight, the sun only showing itself for a few hours a day. Traveling the road today by automobile, the natives watch you suspiciously from their porches. It feels like entering the movie Deliverance. Haskinville is a cluster of a dozen houses, a church, and a store where Neil’s Creek crosses Route 21. But in the late 1800’s it was the epicenter of beekeeping in Steuben County. The Rambler stayed for several days, talked with several local beekeepers, visited a wild bee hunting camp, and tarried at the general store, run by postmaster and notary public, George Silsbee. George’s brother and business partner was William.

William was a beekeeper. He had two sons and a daughter. Both sons became beekeepers, but Myron dreamed of building a hive manufacturing plant to compete with national companies like the A.I. Root, W.T. Falconer, A.G. Woodman Co., and Leahy Manufacturing. In 1911 by, age eighteen, he was managing 160 colonies. In January of that year he laid the foundation of his bee house, a 24×40 foot building which included a bee cellar (for wintering colonies indoors) and a honey processing room. His two storage tanks could hold 9000 lbs. of honey. He soon added a woodshop containing a gasoline engine, saws, and a dovetail cutting machine for hive making.

Tall, good-looking, and a persuasive talker, Myron kept the Haskinville newspaper correspondent and her readers abreast of his activities.

In June Myron catches ten swarms in one day.

In December, Myron buys out another local beekeeper.

In May of 1913, at age twenty, Myron diversified. He built a garage and became an agent for the K-R-I-T motor car company.

In 1913, He published a photo and description of his honey operation in Gleanings in Bee Culture.

In July, Myron hired a man to manage his bees, and in August he harvested 1800 lbs of honey that was put up by his bees in only 6 days.

In 1914, aged twenty-one, Myron hired a second bee man. His ambition grew with every achievement. He displayed his auto cars at county and state fairs. The papers report-Myron goes to Corning on Business. Myron goes to Hornell on Business. Myron goes to Big Creek, Elmira, and Buffalo.

Myron’s plans continued to expand as success followed success. He advertised in the Gleanings in Bee Culture classified section for investors interested in his new beehive manufacturing plant. In 1915 Myron, aged twenty-two, started building a larger addition to his bee house for manufacturing beehives.

More Silsbee news om the Haskinville reporter: In January 1916 he attended the Canandaigua Beekeeper’s Convention, drove to Pennsylvania to buy more bees, and installed a new engine to his machinery.

Myron’s success came too easily. His first setback came on May 3rd of that year. “Myron Silsbee came near having a bad fire in his bee house Friday. He was melting some wax, which took fire but from the timely use of a hand fire extinguisher the whole building would have very likely been destroyed” – Cohocton Valley Times.

In February, 1917 Myron Silsbee bought a display ad in Gleanings for the M.C. Silsbee Company. “Give us a chance to bid on your supplies. We can save you money.” He was only twenty-four years old.

In April, 1917, the United States declared war. Myron registered for the draft but did not become a soldier. The K-R-I-T motor car company filed for bankruptcy and Myron lost his auto business.

By the Autumn of 1917, the United States began sending troops to the Great War to end all wars in Europe. The influenza epidemic that killed an estimated 5% of the world’s population was just beginning. Experts were predicting the worst famine in the history of mankind. Europe was already starving. The U.S. government was rationing wheat (1 ½ lbs. per week per person) and sugar. Because of the sugar shortage, the price of honey was at an all time high. The US government encouraged beekeepers to produce more honey, exempting beekeepers from the sugar rationing, but only for feeding bees.

Ironically, the Winter of 1917-1918 was the worst ever for colony losses. Beekeepers, most likely including Myron, lost 80-90% of their colonies. More people than ever were producing honey, buying bees shipped from the south, and buying bee equipment. Beehive factories were springing up like mushrooms after a rain.

Myron’s fledgling company was long on ambition and short on funds. Any setback could be catastrophic. Less than a year later the Gleanings editor notified his readers: “A letter from M.C. Silsbee says that their bee house, mill, and total contents, were destroyed by fire the previous night with a loss of $5000, partly insured, and that all orders were burned, and they were left with no records of parties who had ordered supplies.” Five thousand dollars in 1918 would be equivalent to about $90,000 today.

The Silsbee Company announced a month later that they would be rebuilding in nearby Avoca, NY. Local history records the existence of a beehive factory in Avoca, but the plant apparently never opened. Six months later, in June 1918, the M.C. Silsbee Company filed for bankruptcy. The newspaper reports that “while temporarily idle, the plant would soon be in operation, putting a large force of men at work.” Two years later, a competitor, the Deroy Taylor Company, bought Silsbee’s remaining stock of woodenware and offered it to Gleaning’s readers at a 60% discount.

Just before the bankruptcy, Myron proposed to Miss Mildred Potter. They were married a year later.

After such a large business failure, Myron couldn’t settle down. In 1920, at age twenty-seven, he moved to Chicago. A year or two later he returned to his home territory and beekeeping. His display ad states, “…if you want the BEST ask for Silsbee’s and accept no substitutes.” He also wrote and sold a booklet-Honey as a Health Food.

He moved to Dansville, NY, twenty miles north of Haskinville and opened an insurance agency. A year later he moved twenty miles farther north to Geneseo, NY.

In 1927 at age 34, he returned, settling near Bath, NY, just a few miles southeast of Haskinville. The newspaper reports that he, his wife, and son James Clair spent a few days in Binghamton, on business. The newspaper doesn’t mention the name of Myron’s wife by name, but seven months later, Mildred had resumed her maiden name and was living with her parents, working as a stenographer at a local business. Mildred made news on July 9th. On her lunch break, she walked to the Avoca Cemetery and swallowed a draught of poison. She was twenty-nine.

Shortly after Mildred’s suicide, the papers reported that Myron was arrested in Macon, Georgia. He had disappeared with a stolen car. Perhaps Myron “borrowed” it, assuming the owner, who was spending the Winter in Florida would never miss it. Someone reported the theft, and the sheriff brought him back.

The papers do not report any fines or jail time, but on this trip or one of his earlier business trips to the south he met and married a girl from Georgia. Louise McLaughlin was eleven years younger than him.

Myron and Louise moved to Babcock Hollow near Bath, NY. Myron worked bees in partnership with his younger brother Lynn. Louise worked at a combination service station and tea room. Autumn of 1928 brought another tragedy. Myron’s three year old son choked on a peanut. Efforts to dislodge it failed and James Clair died. The following Spring, Myron’s father died.

Myron’s second marriage was in trouble. In September 1929, at the start of the Great Depression, Louise accompanied her employer’s wife to Pennsylvania. Her brother, without Myron’s knowledge, escorted her from there to Florida where she moved into her uncle’s hotel. She refused Myron’s entreaties to return to Bath. Myron followed her to Florida and confronted her. When she again refused to return with him, he shot and killed her, and then shot himself.

Wayland Register, March 6, 1930-Friends from this place attended the funeral of Myron Silsbee near Bath last Saturday afternoon.

I thought the M.C. Silsbee story would be an interesting twenty minute talk for the local bee club. Instead it turned into an epic tale of success and failure, scandal, tragedy, and murder set against the backdrop of a World War and the Great Depression.

It’s easy to look back at an era with no mite bombs, hive beetles, CCD, or neonicotinoids and call it the golden era of beekeeping. But they had black and pickled brood, bee paralysis, Paris green, and lead arsenate. While science and culture progress, human nature remains unchanged. Those halcyon days weren’t so halcyon after all.

Copyright 2020 Peter A. Sieling