Lessons of 2022

By: Ed Colby

Oh, fun time!” my cheerful pharmacist laughed when I informed her of my impending colonoscopy. For those of you who have yet to suffer this indignity, here’s what’s fit to print: The procedure is a big nothing. They put you out, and you wake up none the wiser. It’s the unholy day-before, at-home “cleanse” that’s unforgettable. Ask anybody who’s undergone one of these. I was at the pharmacy to pick up my cleanse kit.

Okay, you do what you have to. After 50, colonoscopies become an every five or ten-year ritual, depending on what they find up there. One doctor solemnly informed me that due to my septuagenarian status, this colonoscopy would be my last. I’m not sure what she meant by that, but I can guess.

The hospital scheduling department had proven inept at arranging what should be a slam-dunk procedure. They even got the date wrong. They had both me and the pharmacy thoroughly confused. I told the gal Marilyn, “If the hospital keeps blowing it, maybe I’ll get a vasectomy by mistake!”

To make matters infinitely worse, I had to cancel a fishing day with Paul to stay home and cleanse.

On a Beekeeping Today podcast last Fall, I blurted out the most indiscreet of pronouncements – that in overwintering a total of 200 honey bee colonies over the past three years, I’d lost only five. Because I’m superstitious, I’d kept that under my hat until that particular moment, when I lost my self-control. Yes, I did have a run of very good success, which I attributed to keeping mite populations reasonably low through the Summer and Fall, before giving my colonies an early December oxalic acid dribble, when they were largely broodless.

Bragging generally comes with a price. But I felt I had to drive home that the key to honey bee overwintering is effective mite control. It doesn’t seem reasonable that a bunch of insects could survive a Colorado Winter all huddled together in a simple wooden box. But they can and they do. You might get all worked up over-thinking hive insulation, but I wouldn’t bother. A few subzero nights won’t hurt your healthy colonies. Varroa surely will.

I shot off my mouth at precisely the same time that Varroa were secretly eating some of my colonies alive. A few perished, others merely weakened. But the damage was done. Now will the survivors make it through to March, when you read this?

Okay! Now did I learn anything at all in 2022? Well yeah!

Like never ever assume that your mites are under control. Varroa are having their way with your little darlings, until a test proves otherwise. And when you treat, you need to follow up with yet more testing, because sometimes the cure doesn’t take.

I confirmed my prior belief that Apivar (amitraz) treatments are losing their mojo. They used to be the best of the best. Now sometimes they work, and sometimes they don’t.

I re-learned that Formic Pro (formic acid) sometimes knocks down mite populations.

I was unsuccessful in killing Varroa with Hopguard (hops derivative) strips. I still have some unopened packages. Do you need any?

I learned that Apiguard (thymol) treatments aren’t always effective in cool Fall weather, when our Colorado nighttime lows can dip below freezing.

I learned that you need to pull your honey before you think you should, like in mid-August. If the bees bring in more nectar after you take off the honey supers, they can store it in the brood chamber, and maybe you won’t have to feed this hive before Winter. Now, with the honey off early, you have more mite treatment options, and if one doesn’t work, you have time before Winter to try another!

I learned that cutting up and packaging cut comb honey is a chore, but less so when you leave it on the hive too long, and the bees drag it down to the brood chamber.

From cramming lots of bees and brood into a single brood box for comb honey production, I learned how very resistant colonies with new queens are to swarming, and how extraordinarily productive such colonies can be.

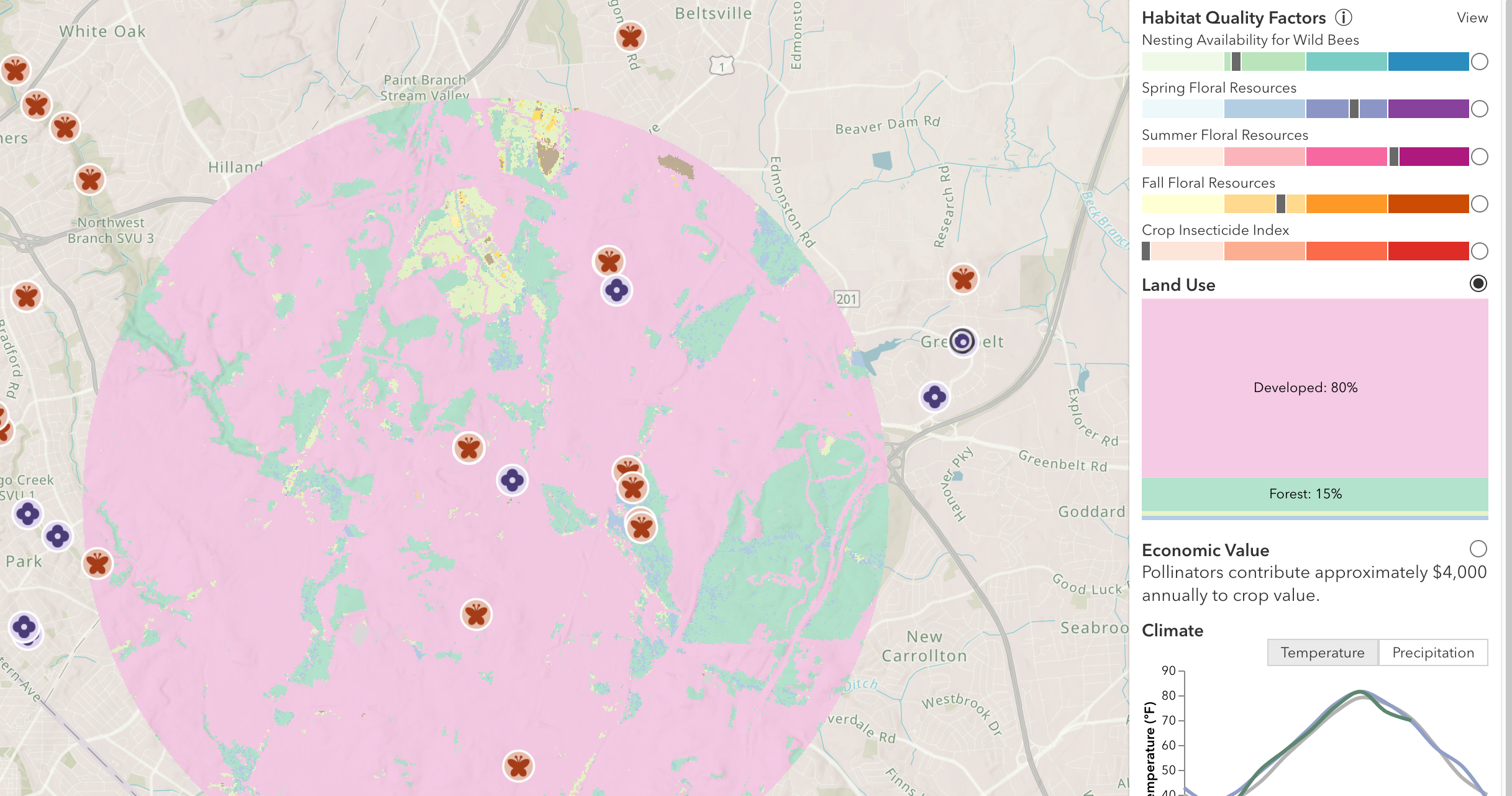

We all know that some honey bee colonies are more resistant to Varroa than others. But don’t forget location, location, location. Some of my beeyards have fewer mite problems than others.

It dawned on me that mites are easier to deal with before they get out of control, and that they’re easier to suppress before the weather gets too hot and your hives get all stacked up with honey supers. So get on it and kill your mites early!

I figured out that if you kill the queen treating a high-mite hive, maybe that’s not such a bad thing. She’s probably the cause of the problem in the first place. This colony will likely raise a new ruler, which is a good thing, and that means the hive gets a brood break, which is a good thing. Better for you to unintentionally kill one queen than for Varroa to take down the whole colony.

Do I sound like a broken record preaching about Varroa? Good. Because colonies overrun with those little monsters are doomed. Point, paragraph, end.

I had my colonoscopy this morning. Afterwards when the doc stopped by my bedside, I said, “I guess this was my last one of these.” He begged to differ. “See you in five years,” he said, as he tossed his business card onto the bed.

Then he was gone, but not before I got the last word. “I can’t wait!”

A Beekeeper’s Life, Tales from the Bottom Board is an attractive paperback collection of 60 of Ed Colby’s best Bee Culture columns, with photos. Signed copies are available from the author at Coloradobees1@gmail.com. Price: $25.