Click Here if you listened. We’d love to know what you think. There is even a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

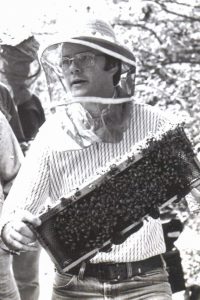

James E. Tew, Fifty Years Ago

What New Beekeepers Should Know About Old Beekeepers

Old beekeepers really do mean to be helpful.

By: James E. Tew

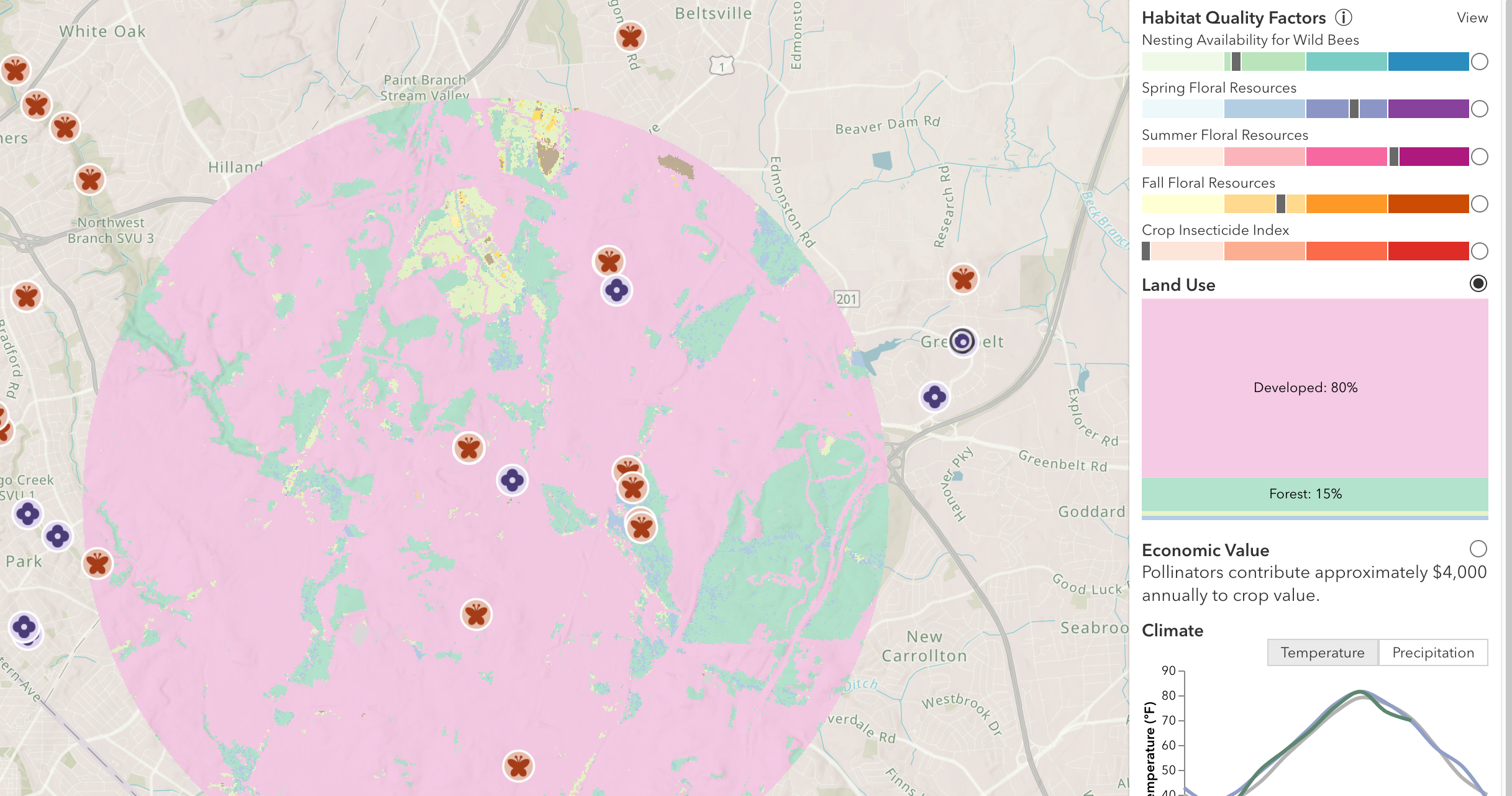

Jumbled thoughts

I know what I want to say, but my thoughts are tumbling over each other. Let me start like this, “When is one an old beekeeper with vast experience – or – when is one an old beekeeper who lives in the past too much?”

For instance, consider five-gallon pails. An experienced beekeeper could say, “Yeah, I certainly remember those old 60# metal tins we used to put honey in. Remember those small, painful wire handles? Remember how the solder joint could break on those handles and drop a 60# can of honey on your foot? But having straight sides, they sure stacked nicely.”

Figure 1. Filling 60# honey tins. Note A.I. Root honey settling tanks

Or an old beekeeper could say, “I remember those 60# honey tins, but I think plastic five gallon buckets are much better. Better handles and much easier to clean and pour honey from (1).” When is information from an experienced beekeeper really helping a new beekeeper and when is it just a walk down memory lane?

Why these thoughts at all?

I’m having these thoughts because everything changes. During the past three to four decades, things have really changed in beekeeping. Mites, small hive beetles, viral pathogens and herbicides have amalgamated to completely restructure beekeeping. So much has changed in management, equipment, bee stocks, honey production and pollination services as to make many established recommendations uncertain or ineffective.

For instance, right now, I should be writing an article for beekeepers describing what they should be doing for Spring management. What should I write? Years ago, Roy Hendrickson (2) discussed Spring management in an excellent article and I did a piece entitled, “A fresh look at the principles of Spring management of bee colonies”, in April 2007. Larry Connor (3) when referring to the 1960’s beekeeping hauntingly said, “…That was a time before tracheal mites, Varroa mites, small hive beetles, CCD, neonicotinoids and African bees…” Good grief! That’s pretty much what I said just a few sentences ago. We seemingly are stepping all over ourselves trying to advise new beekeepers when I sense that old beekeepers need help as much as anyone.

Today, the penalty for mistakes is much greater.

As a beekeeper trained in the ‘70s, I commonly made mistakes but the effects of my errors were rarely severe. Accidentally killing a queen was paramount to a bad day, but queens were readily available and not costly. Not true for today’s beekeeper.

All those years ago, colonies still died during the Winter, but only a few suffered that fate – and so what – you could readily make up the difference by picking up swarms the next Spring. Not true for today’s new beekeeper. Mature colonies were hardy and could reach large populations with little to no intervention by the meddling beekeeper. Splits were easier to make. Today’s colonies are more delicate, more fragile. I don’t know why. Good colonies can suddenly fail.

It seems to me that the new beekeeper is more stressed to get things right quicker and without errors. Increasingly, I have become a bit mouthy about new beekeepers trying to implement all the old management recommendations – plus all the new ones. Reversing brood chambers, frequent requeening, mite treatments, comb replacement, pollen substitutes, feeding medications, tearing down swarm cells… It’s a conundrum. The new beekeeper needs to learn to manage bees, but in learning management techniques, the new beekeeper is punished for making mistakes. (Just so you know, today’s experienced beekeepers are also penalized mightily for making management mistakes, too.)

But I’m ahead of myself – Today, getting bees is much more difficult

All my penalty comments previously assume the new beekeeper was even able to acquire bees. While I am not a fossil beekeeper, in my early bee years, I paid less than $2.00 for a new queen. Today’s new beekeeper can easily pay fifteen times that low price for a queen – if any are even available.

Package bee producers were everywhere. The U.S. Postal System readily shipped them to me. Or I could buy established colonies or splits. They were advertised in farm papers, bee club newsletters and by word-of-mouth. Now, a swarm call is a rare thing. Bees are more difficult to get. Today’s new beekeeper must make careful plans to order packages and arrange to get them, probably through a club or through a bulk order.

Heaven forbid that anything go wrong with the package installation process. Oh, so your package queen died? I hope you can find another one because the package producer is probably not sending extras the way they once did. So here we are again… making errors in installing packages today has greater penalties than it did a few decades ago.

When computers and computer systems were young, I could contact my “University IT people” and they would come troubleshoot my 8088 chip, dual floppy drive computer. Invariably they had to reset some of my dip switches or some such. Does anyone think that I have that kind of support today? Only catastrophic computer issues are addressed (for pay) but for software or general hardware questions – I must go online and search for answers. Today, I am on my own if my computer system hiccups. My computer maintenance situation is similar to modern beekeepers.

Figure 2. A dead queen – more of a problem today.

Years ago, honey bee queens were kinda guaranteed by the producer. Something went wrong – call the queen grower up. This past season, I had some of the queens in my packages die. A couple were dead in the cage before I even released the package. It was not my fault, but I got no free queen replacements. That guaranteed queen thing has nearly passed. I ended up with several six pound packages when I had to combine queenless three pound packages with queenright packages. Let the new beekeeper beware.

Don’t try this at home

For this queen reason and several others, I accidentally worked out a procedure that I may try again. This is not a recommendation for you and may never be one. I was just tinkering.

Of the three-pound packages I had, I took two for a novel release procedure. I released one of the packages in the typical way, but I also opened the second package and released about two pounds of the bees in with the first unit. I used the remaining queen and the last pound of bees to establish a small nucleus colony. So, I essentially had a five pound package and a one pound package.

As I expected, the five pound unit developed quickly. If queen problems had arisen, I had a queen (somewhat) in reserve. Indeed, no problems arose. As the season progressed, I equalized the colonies and currently all is well with the two colonies. The question you should be asking and it’s a question I cannot answer, “Did I grow more bees from those two packages because I used this process?” I don’t yet know, ergo the reason why this is not a recommendation. If I try it again, I will give you an update. Stand by.

Beekeeping information technology then and now

The old system of bee information dispersal is still alive and somewhat well. Hands-on bee education classes are still offered, scores of bee books are available and it seems there is a bee meeting somewhere nearly every night. Bee enthusiasts talking, looking at pictures and people reading all about bees – that hasn’t changed, but other things have changed.

There was a time when I was confident that I knew more about bees than most people in the room but not anymore. The new beekeeper can go to the web for literally anything concerning beekeeping (or anything else). I simply cannot read the thousands of bee-related web pages. Invariably someone has read something that I have not seen.

But here’s the new responsibility for the new beekeeper – not all web-based information is accurate. For instance, it is not a viable procedure to move a colony having laying workers a few yards away, shake the bees from the colony and replace the hive on the original stand. The idea is that the laying workers will not be able to find their way home, but that is not true. Laying workers can find their way home very well. Yet, if you Google the descriptor “shaking bees for laying worker control” many hits are presented that give instructions for this process. Let the new beekeeper beware.

Bee industry compartmentalization

The beekeeping industry has always been an assemblage of subgroups that came together on bee meeting days. Hobby beekeepers, sideline beekeepers, commercial beekeepers, equipment vendors, regulatory people and university/USDA bee professors were some of the typical sub-groups that comprised the audience. Today’s new beekeeper will still be exposed to a segmented industry, but different segments than from a few decades ago. Hobby and sideline beekeepers seem to have been combined. Commercial beekeepers are rare at most small meetings. Commercial beekeeper numbers are fewer. Commercial beekeepers have become so specialized as to nearly be in a different industry than the hobby beekeeper.

Hobby beekeepers – new and old

Many years ago, when Colony Collapse Disorder was in its infancy, I was in a meeting with an Ohio legislative representative when, in reference to hobby beekeepers, he abruptly said, “Don’t ever use the term, hobby beekeeper, again.” He continued that either you are a beekeeper or you are not. No funding agency is going to fund hobbies. I was completely stunned. This one individual had abruptly made a term commonly found in hundreds of bee books obsolete. My very first reaction was to think that the “hobby” term simply could not die but after considering the thought for a few minutes and seeing the opinioned firmness of the representative, I realized that, in Ohio at least, I had probably just witnessed the death of a time-honored term.

Since that time, I have attended two state meetings far removed from Ohio where the presenting speaker admonished the group to delete the hobby word. Today’s hobby beekeeper is just a beekeeper. The term “sideline” beekeeper was always a forced fit, too. So today, within the bee industry, there are essentially beekeepers and commercial beekeepers. Now, I sense that the population of beekeepers has been loosely divided into pre-varroa (old) and post-varroa beekeepers (new). However, even if this is a designation, as old beekeepers pass, the post-varroa group will take over.

Academic beekeepers

Past bee professors were as much a beekeeper as they were a scientist. They commonly attended bee meetings even if they were not speakers on the program. Drs. Walter Rothenbuhler and Basil Furgala are examples of scientists from this era. USDA-ARS scientists were governmentally funded and not encumbered with the obligation to get outside grants. They were encouraged to work on problems that had immediate and direct effects on the industry. For instance, B.F. Detroy was a USDA-ARS beekeeping engineer who worked on projects like developing steam-heated uncapping knives, insulating beehives and pollen traps designs.

For many legitimate reasons, academic beekeeping today is nearly completely removed from the practical bee industry. The studies they implement are specialized and conclusions drawn are complicated. In eras past, academic beekeepers were simply doing their jobs when working with the bee industry. Today’s academic beekeeper is stressed to get outside funding and to succeed inside the broader scientific community. That internal scientific success can have little to do with the day-to-day life of the typical beekeeper. This is not a good or bad thing, but it is a different thing from the way academic beekeeping was years ago.

Still jumbled

My thoughts are still muddled, but I know what was an uncertain feeling as I stood before the group at a recent county meeting. It was a modern group made up of new and old beekeepers. Those of us in the old group have paternal feelings and want to help these new beekeepers at every turn. Even this magazine recently has had articles on how to nurture new beekeepers. That sounds like current recommendations for helping bee colonies. We have the best intentions but our aid programs frequently harm our colonies as much as they help.

True, old beekeepers can help with the mechanics of beekeeping, but today’s bright-eyed, eager, new beekeeper never knew bees without mites, poor queens, herbicides and imported honey. They don’t expect bee professors to grace their meetings. Instead, they will keep bees in town more often than the countryside and when they need information, they will search the web or blog or podcast. In a pinch, they will use old-fashioned email. When requesting information, they will rarely use a land-line phone and will never, ever write an actual letter.

Figure 3. A batch of new beekeepers. Can you pick them out?

My last thought on the subject

Due to mites, insecticides, viruses, bee diseases and imported honey, in many ways, we are ALL new beekeepers. Old beekeepers know more about the mechanics and fundamentals of bees and beekeeping but the new group knows more about today’s way of communicating and implementing modern beekeeping principles. New beekeepers are not saddled to the past. New beekeepers are living in their present. To survive and thrive in this changing bee world, old beekeepers probably need new beekeepers as much as the new needs the old. We are all in the same bee boat and for all of us, it’s a new boat.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

tewbee2@gmail.com

Co-Host, Honey Bee Obscura Podcast

Co-Host, Honey Bee Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com

(1) But now I am wondering about the microplastic content of plastic honey buckets when crystallized honey is heated in plastic buckets.

(2) Hendrickson, Roy. 2008. Spring Management of Overwintered Colonies. Bee Culture, Feb. 2008. Vol 136, No.2

(3) Connor, Lawrence. 2009. Changing the way we train new beekeepers. Bee Culture, Sep. 2009 Vol 137, No. 9