By: Peter Sieling

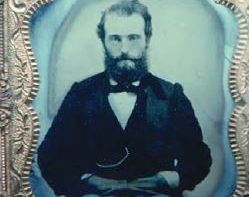

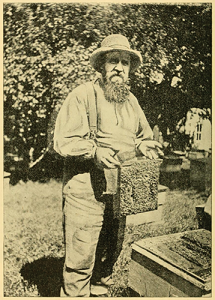

On June 3rd, 1918, 100 years ago, Gilbert M. Doolittle died at age 72. Today he is remembered as the father of commercial queen-rearing. His book, Scientific Queen Rearing remains a classic work in apicultural literature. That book is just a small part of the enormous contribution Doolittle made to bee culture.

Doolittle was one of the most prolific apicultural writers of all time. He wrote thousands of articles for seven periodicals over a forty-eight year span. He read all the beekeeping papers of the time and tried out the recommendations of other authors. Woe to the person who made claims based on theory rather than experience! Some of his most entertaining articles consisted of verbal sword fights with other beekeepers.

Doolittle was one of the most prolific apicultural writers of all time. He wrote thousands of articles for seven periodicals over a forty-eight year span. He read all the beekeeping papers of the time and tried out the recommendations of other authors. Woe to the person who made claims based on theory rather than experience! Some of his most entertaining articles consisted of verbal sword fights with other beekeepers.

Doolittle’s advice was practically the final word on any discussion related to beekeeping. People traveled from all over the United States to visit him, by train, steamer, and bicycle. His techniques and inventions weren’t original. He took other peoples’ ideas and improved them. Artificial queen cell cups, the solar wax melter, and the division board feeder are some inventions he improved. Many of today’s management techniques were perfected by Doolittle.

Doolittle wrote very little about his personal life, except as it related to beekeeping. Most biographical information comes from people who visited him and from stories published from his talks at beekeeper conventions.

Gilbert M. Doolittle was born near the small village of Borodino, in the Finger Lakes region of Central New York State in 1846. His father was a farmer, “poorly supplied with this world’s goods”. He kept Gilbert at work on the farm, so he received only a limited education. Doolittle once recalled sitting in the classroom the day the school commissioner came to examine the school. The teacher pointed out Gilbert as the “biggest ignoramus in the school.”

When Gilbert was 10 years old, his father bought a colony of bees. Four years later, the Doolittle apiary had grown to 15 or 20 colonies, all in box hives. His father gave him a small swarm of his own. He left it some distance from the house and on coming home from school one morning found that someone had killed the bees and stolen the honey. Shortly after, his father’s colonies succumbed to American foulbrood and had to be burned.

Ten years later, at age 24, Doolittle caught what they used to call “bee fever”. He acquired two hives and began reading all the books he could find on beekeeping and subscribed to several beekeeping papers.

Doolittle’s father was not pleased with his son’s interest in beekeeping. Gilbert was neglecting his farm work. One day while Gilbert was upstairs in the house he heard his father talking to a neighbor, “I have always wanted and expected that Gilbert would be a farmer. I have hoped and prayed that he would make a failure of beekeeping, but it looks now as though he were going to succeed in spite of my hopes and my prayers.” A year later, Gilbert left the farm and made beekeeping his specialty.

Doolittle corresponded with Elisha Gallup, a prolific beekeeping writer of the day. Gallup patiently answered all Doolittle’s questions. The stack of letters, according to Doolittle was three or four inches high. In gratitude for Gallup’s help, Doolittle continued the favor, answering all questions sent to him by other beekeepers.

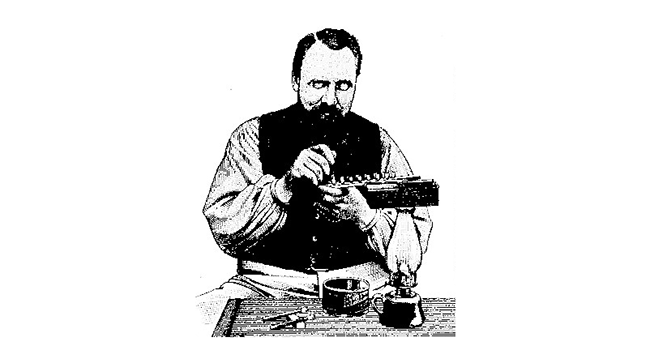

He describes the next 30 years “as little less than one round of endless pleasure.” He wrote, “I dreamed of bees nights, and thought of them during my waking hours to an almost absorbing extent.” Doolittle’s “endless pleasure” included doing everything himself. Besides managing two beeyards, he made equipment in his workshop powered by a steam engine. He answered all his voluminous correspondence, wrote articles for the various magazines, handled all his queen shipping (local people said Doolittle’s queen business constituted half of the local post office’s volume). In addition he kept up a garden, took care of the horse and was an active member of his church and town.

He describes the next 30 years “as little less than one round of endless pleasure.” He wrote, “I dreamed of bees nights, and thought of them during my waking hours to an almost absorbing extent.” Doolittle’s “endless pleasure” included doing everything himself. Besides managing two beeyards, he made equipment in his workshop powered by a steam engine. He answered all his voluminous correspondence, wrote articles for the various magazines, handled all his queen shipping (local people said Doolittle’s queen business constituted half of the local post office’s volume). In addition he kept up a garden, took care of the horse and was an active member of his church and town.

Doolittle met and fell in love with Frances Rosetta Clark. She has been described as an “invalid” and “lame.” Friends tried to dissuade him from marrying her. His response to them was, “I like her even better for her misfortune.” They never had children.

Doolittle began writing in 1870, publishing his first article in the Apiculturist and Home Circle. His first letter in Gleanings appeared in its first year of publication in 1873:

“I have got off 1600 lbs. box honey, which I have sold for 25 cts. per pound. Extracted sold for 14c. I have also worked another small apiary for half of the honey, from which I have taken 900 lbs. I have also worked a 150 acre farm with the help of one man, and to tell the truth I am nearly worked out.”

He eventually sold the farm, keeping twenty acres for his honey and queen business.

In 1880, Doolittle’s father suffered an unspecified illness and needed care. Doolittle reduced his colonies from 250 to about 100. After his father’s death, Doolittle supported his mother and sister. By 1907, ill health forced him to take on P.G. Clark as an assistant. Little is recorded about Clark, except that he lived in nearby Marietta and spoke at a couple bee conferences. He may have been a relation of Doolittle’s wife, Frances Clark.

In 1913, Doolittle’s wife suffered a stroke and he took over full care of her. He kept five colonies for relaxation, and continued to write.

Doolittle quotes:

1907 p.392

“…our time for study and preparation all along the line of bee work is during the winter months; and he who takes time by the forelock is the one the most likely to succeed.”

1907 p. 623

“…each season adds new thoughts, new complications, new zest, new energies, new determinations, etc., till the one great whole gives an indescribable pleasure to beekeeping not found in any other pursuit. And this pleasure can be grasped only by the one who is not turned aside by trifles. Over the door of apiculture stands written in letters of fire, ‘lazy and shiftless persons need not apply…’”

One hundred years ago Doolittle died of “heat prostration complicated by having contracted a severe cold.” It would be interesting to know what that would be called now. He had written his columns for the whole year during the winter months, so like a ghost he kept reappearing through the December issue of Gleanings, when the editor wrote,

“…the pen has now dropped from the lifeless hand, and he will appear no more in these pages, save as a quoted authority and memory.”

Doolittle on Stinging – 1915

Do bees dislike black? In my younger years I accepted the idea as the truth. One day, four of us met at one of the apiaries, I wearing a black felt hat, the other three wearing straw hats. It was not long before Doolittle was the target for apparently all of the cross bees in the apiary, the bees getting on that black hat and stinging very much as they will in one’s hair. Of course the trouble was in the color.

A few weeks later we met in another apiary, I wearing a white felt hat, and the others had hats of various shades, but none black. To my surprise, I was again the target for the cross bees. They stung away at that hat the same as they had done when I wore the black one. Again we met at my own apiary; and as this was a very warm day we all wore straw hats of about the same color. To my surprise, I was again the target for nearly all the cross bees we happened to stir up – not that the bees attacked my hat more, but they seemed to want to sting Doolittle more than any of the other three.

Then I concluded that their dislike was for my person. And I have found this to be so in the majority of cases wherever I have visited with beekeepers at different apiaries. I have often felt almost ashamed of myself when being obliged to hide my head in a bush or call for a veil when others had no trouble. But of this I am certain: Bees have a great antipathy toward any clothing that is fuzzy or of a hairy nature, and such should be avoided in the apiary.

Literary contribution to Beekeeping

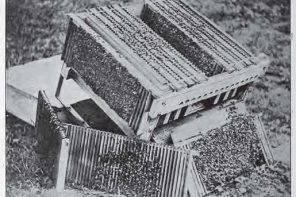

Doolittle’s book Scientific Queen Rearing introduces the artificial queen-cell cup as well as the production of queens above a regular hive with just a queen excluder between the two compartments. The book received a dubious review in Gleanings when it was first published. Over time it became the standard practice among queen breeders.

Doolittle also wrote two pamphlets. The Hive I Use describes his version of Elisha Gallup’s hive with frames approximately 12 inches square. Doolittle stubbornly stuck to his Gallup hives for his queen-rearing, but used Langstroth hives in his out yard. Rearing Queens is a pamphlet based on articles he had published in magazines.

His last book, A Year’s Work in an Out-Apiary first appeared in serial form in Gleanings in Bee Culture in 1906. It describes how he managed to harvest a maximum quantity of comb or section honey with only 12 visits to the bee yard. Most importantly, he claimed to have conquered the problem of swarming in an unsupervised bee yard. Doolittle never wrote a comprehensive, how-to-keep-bees textbook, stating that there were so many good books already, plus he already covered it all in his articles in the bee papers.

The bee papers of a century ago were like a slow version of the internet today. There was a great deal of discussion among writers, readers, and editors. Doolittle frequently ruffled feathers by challenging other beekeepers’ pet theories. Some of his liveliest writing occurred when he disagreed with other beekeepers. “Truth and facts are such keen weapons that theory and error cannot stand against them.”

His column in Gleanings in Bee Culture started out as Seasonable Questions. Later it was changed to Conversations with Doolittle. With his declining health and his wife’s illness, and the fact that there is only so much you can write about bees over 48 years in seven papers without repeating yourself, his writing lost some its sparkle in the later years.

Doolittle quotes:

“The idea that bees ‘work for nothing and board themselves’ must be banished from our thoughts…. Successful bee-keeping means work, and lots of it, for a man with brains enough to know that he must leave no stone unturned that tends toward success.”

“We are here for the good we can do, and if we know something that will be useful to our fellow-men, we should impart that knowledge to them as long as health and strength will permit.”

Doolittle’s activities regularly appeared in the local papers:

Cazenovia Republican, Sept. 30 1875

Mr. G. M. Doolittle, of Borodino, brought to this city Friday, four wagon loads of pure and beautiful honey, which he sold for twenty-five cents per pound. The combined weight of the packages was 7,000 pounds, amounting in money to $1,750 (the equivalent of approximately $38,000 in 2018).

Sometimes the papers get their facts wrong. Even Doolittle wouldn’t get this sort of yield:

The Cortland Standard, August 30, 1877

G. M. Doolittle, of Borodino, Onondaga County, had sixty-seven swarms of bees at the opening of the season. He has taken four tons of box and 750 pounds of extracted honey from a single swarm. He has 157 colonies now.

NY Evening Post, Aug 8, 1884

G. M. Doolittle, of Borodino, NY, has kept for the last eight or nine years an average of fifty hives in connection with the fruit business, and although taking but a small part of his time, he has averaged over $1,000 a year from the sales of his honey. Last year he took 4,000 pounds of linden honey, all of which his bees gathered from a linden forest six miles distant.

Excerpt from The Otsego Farmer, August 15, 1890

“One lesson every successful beekeeper has to learn sooner or later…that is to keep his colonies of bees strong… look after the health and comfort of the bees rather than after honey. If they are kept healthy and strong, the honey will flow freely as a consequence…It is with bees as with birds and beasts—the better they are cared for the more valuable and profitable they become. The principles of life are about the same in all animated things.”

The Skaneateles Press, August 25, 1893

G. M. Doolittle, the Borodino apiarist; has received an order for $100 worth of Italian queen bees for shipment to Australia, via the Pacific coast.

The Evening Herald, Nov. 27, 1896

Natural Gas Discovered and Doolittle has a Close Shave

A group of men, including G. M. Doolittle, investigated a crevice from which issued a stream of natural gas. Fitting a blowpipe over the crevice, they boiled water, burned twigs and melted lead. Mr. Doolittle also quite unexpectedly found that gas would shave a man in less than a second.

Doolittle at the Theatre – 1898

Take a spool of white basting cotton. Drop it into your inside coat pocket, and, threading a needle with it, pass it up through the shoulder of your coat. Leave the end an inch or so long on the outside of your coat, and take off the needle. Four persons out of five will try to pick that thread off your shoulder as soon as they see it, and will pull on the spool until it actually does seem as though they are unraveling not only your clothes, but yourself.

Fixed as above, I was at a theater in Boston on one occasion. It was in the most interesting and pathetic portion of the play, when suddenly I felt something tugging at the basting cotton that I myself had clean forgotten. Half glancing around, I saw a woman – a total stranger – yanking at the thread. Her face was scarlet. She had pulled out about 10 yards, and was now hauling in hand over hand. Rip! rip! went the thread. Hand over hand she yanked it in. The aisle was full of it. “For Heaven’s sake! Will it never end?” said she above her breath. I sat perfectly still while she pulled.

The whole section of the house soon got on to it. They didn’t know whether to laugh at me or her, but sat and looked on amazed at the spectacle. At last as the cotton got twisted around her watch chain, over her eyeglasses, in her hair, and filled her lap, I turned around and, producing the spool from my pocket, said, ‘I am sorry I misled you. You see I have about 124 yards left, but I presume that you don’t care for any more tonight. The woman was a modest sort of lady in appearance. Her face was as red as fire, even to her ears. She looked at me and then at the spool. She changed color once or twice, and when the crowd caught on, the laughter was so uproarious that I almost repented me that I had done the thing, because it placed both of us in a rather ludicrous light.